Europe’s luxury trap is not what it seems

Selling status and heritage is a modern and sometimes innovative business

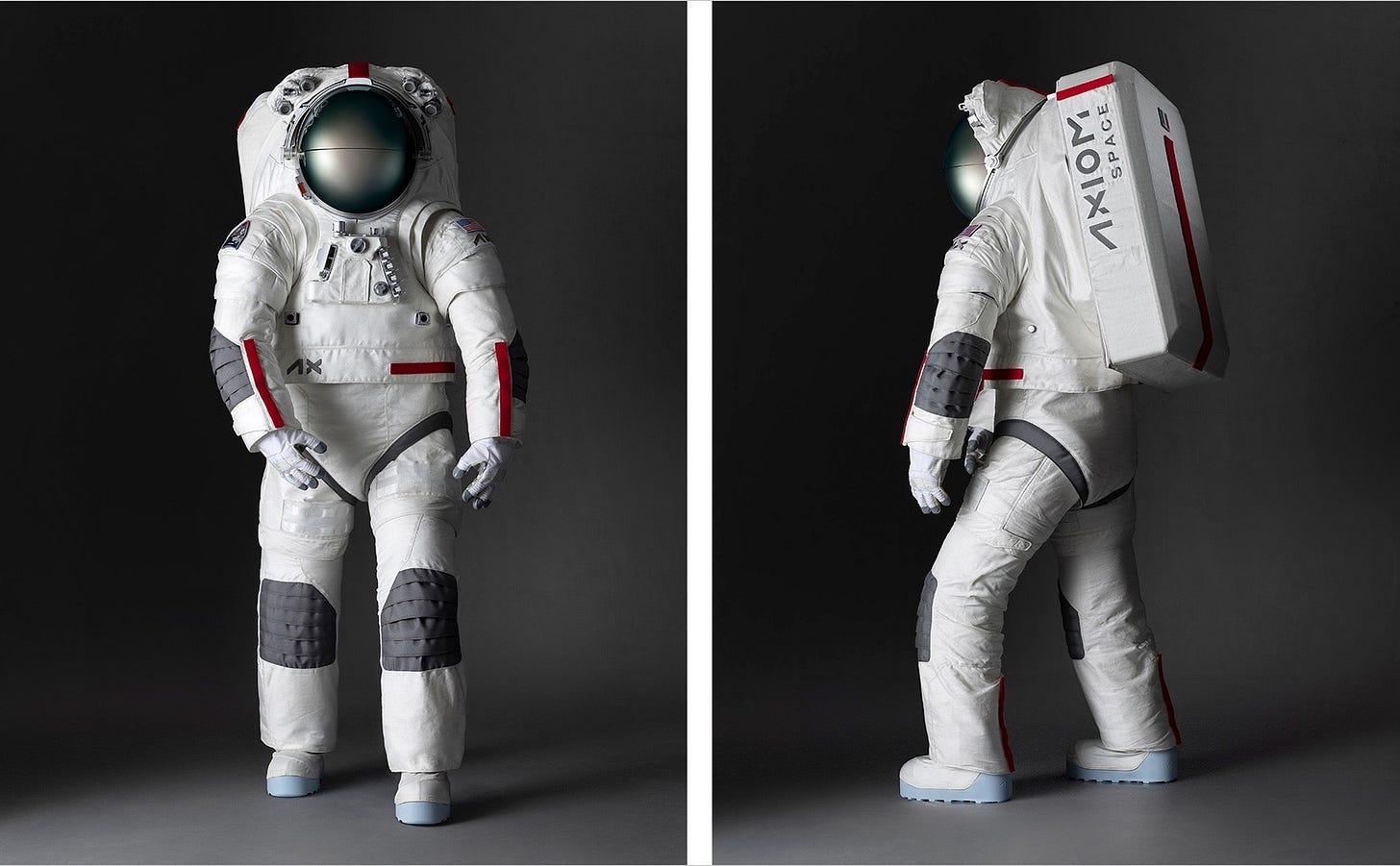

In 2026, when NASA sends astronauts to the moon for the first time in over 50 years, their suits will bear the red stripes of the Italian luxury brand Prada. Though better known for sunglasses and handbags, Prada has expertise in high-performance composite materials, thanks to its work on yacht racing apparel. So the Texas-based company Axiom Space enlisted the fashion house to help with the outer layer of its NASA space suits, which were unveiled last week. The garments are designed to keep out fine lunar dust and handle extremes of temperature, though as those red stripes suggest, Prada’s styling advice was welcome too. The moonwalks will be major media events after all.

This story caught my attention because it runs counter to a common view of the luxury industry as a symbol of European decadence. There are few areas where European firms are undisputed world leaders, but luxury is certainly one of them. Europe has nine of the ten most valuable luxury companies in the world. Nowhere is better at high-end clothing, jewellery, handbags, perfume, champagne, watches, and prestigious car marques. The recent slump in luxury shares came after a post-pandemic boom period, when they dominated the European stock market in the same way as tech companies dominate the American one. The industry is made up of large conglomerates, many of them French, each of which control numerous brands. LVMH owns 75 luxury producers, from Christian Dior to Veuve Clicquot. It is Europe’s second most valuable company, having lost the top spot to Danish drug maker Novo Nordisk last year, and its owner, Bernard Arnault, vies with Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos for the title of world’s richest man.

According to critics, mastering the arts of opulence is nothing to be proud of at a time when Europe still has no tech giants to match those of Silicon Valley; when the once-mighty German car industry is being trounced by technologically superior Chinese rivals; and when the economist Mario Draghi is warning, in a much-cited report, that the E.U.’s innovation deficit amounts to an “existential challenge.”

Europe, we hear, has become a museum; it offers the world a sublime heritage in food, art and architecture, but this cannot pay for its costly social spending commitments. Likewise – and by contrast to large-scale, cutting-edge industries like software and pharmaceuticals – luxury goods are artisanal products, trading off a reverence for tradition, made in small numbers through time-consuming craft practices. It takes 40 hours, not to mentions years of apprenticeship, to produce a single Hermès Birkin handbag, using stitching techniques that cannot be mechanised.

As Ruchir Sharma put it last year, “building a knowledge economy on crafts dating back to the 17th century is arguably a backwards move” for a continent struggling to modernise. “If it’s not clear how much smartphones boost productivity growth,” Sharma adds, “it is safe to say that French perfume and Italian handbags contribute even less.”

To be sure, the success of luxury firms is a symptom of inequality, and provides little by way of general economic uplift. When investors pour capital into boutique companies that serve small numbers of people, employ even fewer, and invest very little in research and development, ordinary Europeans are unlikely to benefit much. But artisanal luxury goods are not themselves archaic. They are as much part of 21st century capitalism as smartphones and electric vehicles. As I’ve argued before – most recently in relation to Harrods department store – heritage is today less a spiritual asset belonging to a particular place and culture than a body of symbols, stories and products to be marketed to wealthy foreigners. Europe’s luxury sector is a form of specialisation; it answers the demand of Chinese and Middle Eastern elites for status symbols, in the same way as those regions answer Western demand for manufactured goods and fossil fuels.

Since this strategy creates big profits – as Sharma notes, European luxury firms have higher margins than US tech companies do – it generates pressure for further growth and expansion into new areas. Thus luxury brands have been associating themselves with a wider range of sports, notably football. In 2022, a Louis Vuitton campaign featuring Christiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi scored a record number of Instagram likes. Prada sponsors Chinese footballers, basketball players and table tennis stars. Even as luxury producers try to maintain their aura of heritage, the search for new markets and publicity will involve them in projects that are far from traditional. Space suits with red stripes are one example of this; high-tech apartment buildings designed by car marques like Porsche are another.

The notion that modernisation requires old companies to be displaced by new ones may be an American prejudice. Japan has among the world’s most technologically sophisticated cultures, as well as the highest concentration of very old companies. In 2019, researchers at Teikoku Data Bank found over 33,000 Japanese companies that are more than a century old – these are called shinise – and many of them go back much further than that.

One of the reasons commonly cited for this staying power relates to the idea of “core competency,” meaning the fundamental strength of a business which lies deeper than the products and services it happens to be trading at a particular moment. Understanding this competency allows firms to evolve and adapt. Nintendo was a playing card company that found its way into electronic gaming systems, having decided its strength was providing fun. Hosoo, a firm founded in 1688, used its weaving expertise to move from kimonos (a traditional garment) to carbon fibre manufacturing. Another seventeenth century enterprise, Sumitomo Forestry, has helped design a wooden satellite that is due to enter orbit this year.

As Prada’s own lunar excursion suggests, European luxury firms could be capable of similar dynamism, especially as they have maintained local expertise rather than outsourcing production to other parts of the world. Take German orthopaedic shoemaker Birkenstock, a centuries-old, family-run enterprise of a kind that would not be out of place in Japan. Its core competency is making extremely comfortable footbeds, using cork, latex and other materials. These have variously been treated as health products, fashion statements and affordable everyday shoes. Now, with financial backing and advice from LVMH’s Arnault, they are being reimagined as luxury products. This shift relies not just on Birkenstock’s heritage, but its potential for innovation: the plan is to develop plastic shoes for markets in China, India, and the Middle East.

If Europeans could see one part of their economy thriving, few of them would choose perfume and handbags. E.U. leaders would doubtless prefer to be leading a lunar mission than providing the wardrobe. Still, to dismiss the luxury industry as decadent and old-fashioned is to fall for its own marketing pitch.

Wessie, nicely done, as always. But I think "decadent" is ambiguous, and that creates a confusion in your essay. On the one hand, decadent implies decline. But rich societies need markers, too ("Veblen goods") and LVMH and its ilk are happy to provide them. So lots of European companies can be have thrived by selling signs of being rich, especially into the burgeoning class of newly rich folks. (Downturns rough, see Mercedes.). But that hardly exhausts "decadent." Jeff Bezos's largest sailing yacht in world with lascivious girlfriend on prow is, also, decadent. I'm not exactly talking about inequality, though there is that. More bad taste. So "decadent" as vaguely moral and aesthetic problem. And are we so sure that European luxury, at least a lot of it, isn't in fact guilty as charged on that score? You're the design guy . . .

Keep up the great work.