A Century of Art Deco

The marriage of French style and American ambition

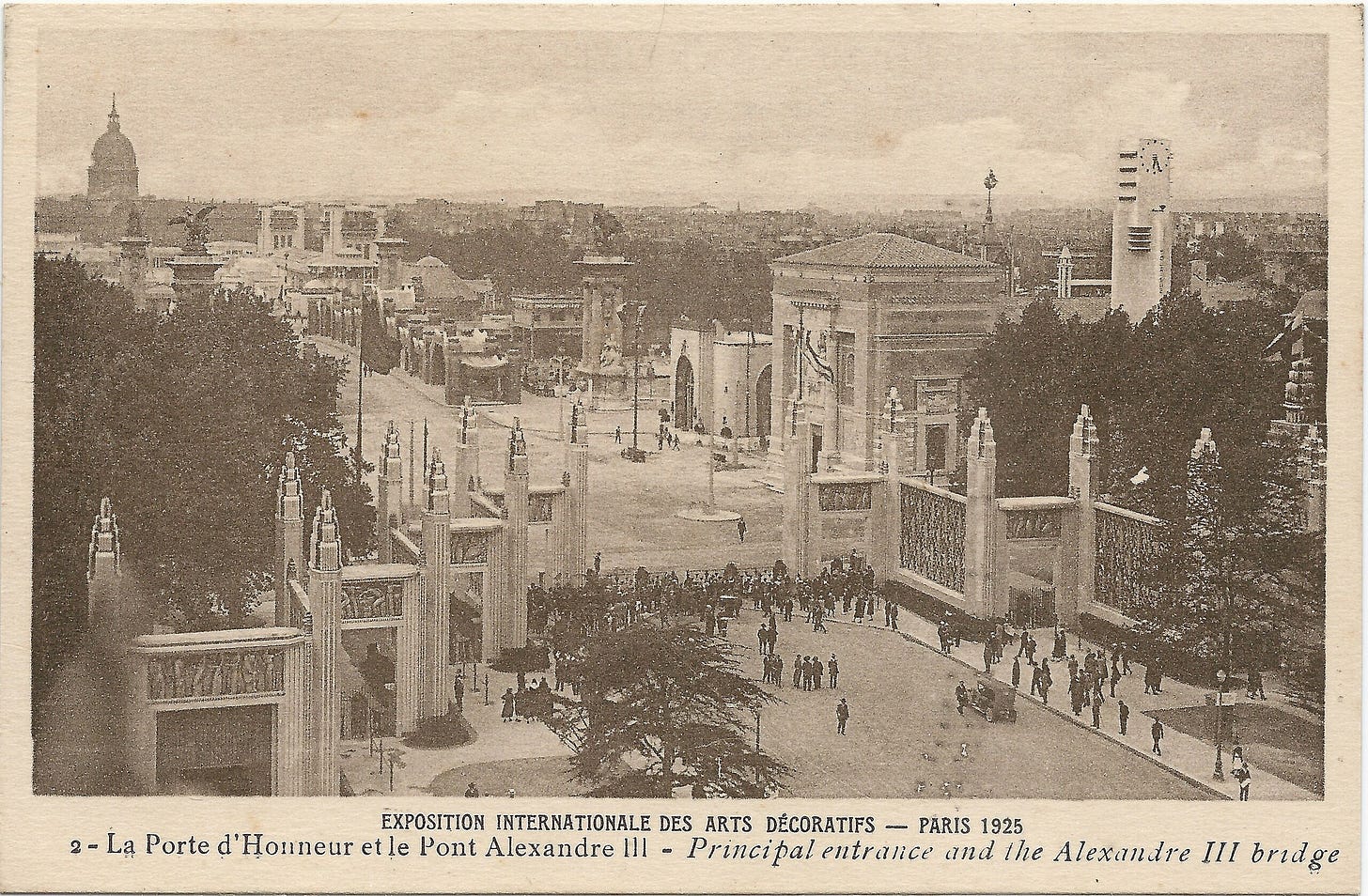

In early November 1925, exactly one hundred years ago, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes closed in Paris. It had been quite a show. In six months, some 15 million people had visited an exhibition area occupying 57 acres of central Paris, bordered by twelve grand gateways. Though it was an international fair, French designers and department stores had occupied two-thirds of the pavilions. It is thanks to their work that the event is remembered in connection with one style of design in particular, the style which would later take its name from the 1925 expo: Art Deco.

In the years that followed, Deco was formalised as a visual language of sensual curves and stepped profiles, geometric motifs, and classical proportions with a dramatic modern accent. A century after its birth, its appeal remains strong. The Steinway Tower, a supertall skyscraper recently erected on “Billionaire’s Row” in New York, is one demonstration of the style’s lasting ability to evoke a sense of luxury (Edwin Heathcote aptly describes the building as “the purest illustration of architecture as an expression of surplus capital”). Art Deco’s streamlined shapes and smooth, polished surfaces have been a regular fixture in this century’s craze for the retro. Most influentially, Deco has become central to the aesthetic universe of Elon Musk, inspiring the logo of the entrepreneur’s social media platform, X, and the sleek appearance of his Tesla Cybercab.

Yet our intuitions about Art Deco obscure the style’s true significance in history. We think about Deco in relation to the gaudy glamour of Gatsby era America, but its character stems from a French tradition of luxury crafts that dates back to the 18th century. This was a cultural movement – maybe the first – that originated in Europe but was given its fullest and most memorable expression in the United States. It was not an American style, but it became one; it represents the moment at which the currents of cultural influence began to reverse, and the attractions of the American high life and American popular culture started to wash over the old continent in earnest.

The exhibition that gave Deco its name had originally been scheduled for 1914, but was delayed by the outbreak of the First World War. And like that seismic conflict, it was an expression of Franco-German rivalry. In the first decade of the twentieth century, German industrial design had burst onto the scene with the distinctively modern, utilitarian products of the Deutscher Werkbund, precursor to the Bauhaus. These were simple but striking objects, mass-made for the machine age, and as Anne Massey explains in her history of interior design, they represented a challenge to the status of French designers as Europe’s dominant tastemakers. The French response was a conscious effort to move past the lyrical forms of art nouveau and to develop a more modern aesthetic, without, however, abandoning the traditions of fine craftsmanship and luxury production which France had sustained since the age of its Sun King, Louis XIV.

Deco thus displays an ornate classicism familiar from earlier centuries of French design, combined with elements that were fashionable in artistic circles of the early twentieth century, notably geometric patterns and exotic motifs borrowed from the cultures of the East. Allusions to Egypt became especially popular after the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 – many a provincial cinema would soon be adorned with semi-circular sunburst motifs – but this too had been anticipated by France’s own traditions: Egyptian symbols featured prominently in Napoleon Bonaparte’s Empire style, a considerable influence on Deco.

One could think of Art Deco, then, as a counterweight to the emergence of Modernism as the aspiring language of industrial modernity. Where Modernism was functional and economical, Deco was lavish and, well, decorative. Where Modernism argued for standardisation, Deco insisted that a space should express individuality. Where Modernism was egalitarian, Deco celebrated beauty and taste. And where Modernism was universal, Deco brought together an assortment of different periods and cultures. As it happens, the 1925 exposition would also be an important landmark in the Modernist story, not thanks to any German exhibit (there were none; the French organisers deliberately sent the invitation too late) but because of the Pavillon de l’Éspirit Nouveau, an audacious project by the young Le Corbusier. Inevitably, hybrid “Moderne” styles soon emerged, incorporating industrial materials and Modernist aesthetics into swanky upmarket interiors.

To understand the appeal of Deco’s opulent fantasies during the 1920s and 30s, we need only recall that this was a time of immense upheaval. In the aftermath of the First World War, Europe was rocked by economic instability, by class war and revolution, by the on-going collapse of long established social and political orders. Deco offered an escape, or at least a distraction. It was, as Catherine Slessor writes, “a soft style for hard times, a suave companion on the road to hell.” Slessor notes that Deco has also tended to revive at times of insecurity, such as the 1970s. (It is intriguing that another design movement of that decade, postmodernism, shares Deco’s promiscuous approach to borrowing from other times and places, as well as its appetite for make-believe). Over the past decade, Deco has again rekindled in an atmosphere of turmoil. Its appearance in luxury apartments, high-end shopping malls, and the retro-futurism of Elon Musk suggest that it has become especially suited to packaging wealth and technology as anaesthetics against an anxious world.

Deco did not initially take off in Britain, where the preferred form of escapism during the interwar years, as at other times, was a return to the warmth of its own past. Louche Parisian fashions were an awkward fit alongside the mock-Tudor facades and Jacobean furniture of the new English suburbs. In the United States, by contrast, Deco was enthusiastically embraced. From our current perspective, when America acts as a relentless pace setter for European culture, the strangest aspect of the 1925 exhibition is that the U.S. considered itself too backward to take part. Having consulted leaders in the arts and business, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover judged that American designers could not meet the requirement for modern work. Instead, he sent a delegation of more than 100 envoys, representing a range of design fields, to attend the exhibition and take notes. Furniture from the Paris expo was subsequently displayed around the United States, notably at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, while dozens of American museums and department stores held their own exhibitions of the new French fashion.

Whether this affinity for Deco came, as Massey suggests, from a young nation’s desire for a new decorative language, or less charitably, from a parvenu’s love of ostentation parading as refinement, the Americans proceeded to make the style their own. Some of the great skyscrapers built in this period – the Chrysler, the Empire State, the superb Chanin Building – became temples of Deco, as did the enormous picture palaces where thousands gathered to enjoy the new medium of cinema. Those audiences saw Deco on the screen too, as Hollywood set builders embraced the style. Then, in the 1930s, product designers hit upon an authentically American adaptation of Deco in the form of streamlining, a look derived from the dynamic profiles of cars and trains. Sumptuous, swishing curves, rendered in shiny chrome plating or smooth Bakelite, were applied to everything from gramophones and radios to fridges, telephones and cameras.

In 1928, the designer Paul T. Frankl, who had emigrated to the United States from Vienna, declared that “the foundation for a distinctive American art is already being laid.” The lasting association of Deco with American achievements in architecture, film, and mass production is a testament to the nation’s energy at that moment. Yet the return of Deco today cannot, of course, signify the same thing. Even if it encases the most advanced technologies, the style now looks backward as well as forward. Much as Art Deco once carried the prestige of France’s design heritage, it now invokes the classical era of American ambition a century ago.

I was recently at Chateau Valençay, the country seat of France's greatest statesman, the charismatic "lame devil" Prince Maurice de Talleyrand, an 18th century man of refined taste and style. In his leisure the prince of diplomats was much interested in art, design, and modern technology.

I have said elsewhere that could he time-travel, after orientation and study of modern history, the pragmatic and far-seeing Talleyrand would be a far cannier advisor to western leaders grappling with the problems of Putin, China, and the Middle East, than anyone now living. He would today, I think, have furnished his magnificent palace with at least one salon, and perhaps added a guest-house, in the Art Deco style.

An exceptional interview that Lech Walesa, the man who had never read a single book but thought and spoke as if he had the essential books of the world in mind, gave to journalist Oriana Fallaci in 1981, in Gdansk, ended with the following sentence: “if I get to Heaven, I will save a place for you.”

For the splendid decorations of the facade of the Chanin building, their designer, Chambellan, has certainly gotten to Heaven. In 50 years – or maybe more, if we become Methuselahs again – they will be joined by Franz von Holzhausen, the extremely inspired designer at Tesla.

There is so much need for art...