Napoleon's Furniture

How the little corporal used design to express his world-shaping ambition

The design of chairs is not normally listed among the achievements of Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s famous post-revolutionary emperor, but the importance of furniture should never be underestimated. Besides redrawing the map of the Europe, establishing institutions and writing law codes, Napoleon should be seen as a seminal figure in the development of modern design.

Napoleon embodies modernity in its heroic phase. He was celebrated as an icon of both Romanticism and the Enlightenment; a symbol of unstoppable willpower who crossed the Alps on his rearing wild-eyed stallion (or at least was painted by doing so by Jacques-Louis David), as well as the ultimate Enlightened despot, aspiring to replace feudal superstition with the universal principles of Reason. Between these two sides of the Napoleonic myth we can glimpse his remarkable understanding of modern authority, which rests on the active creation of order in a world of turbulent change.

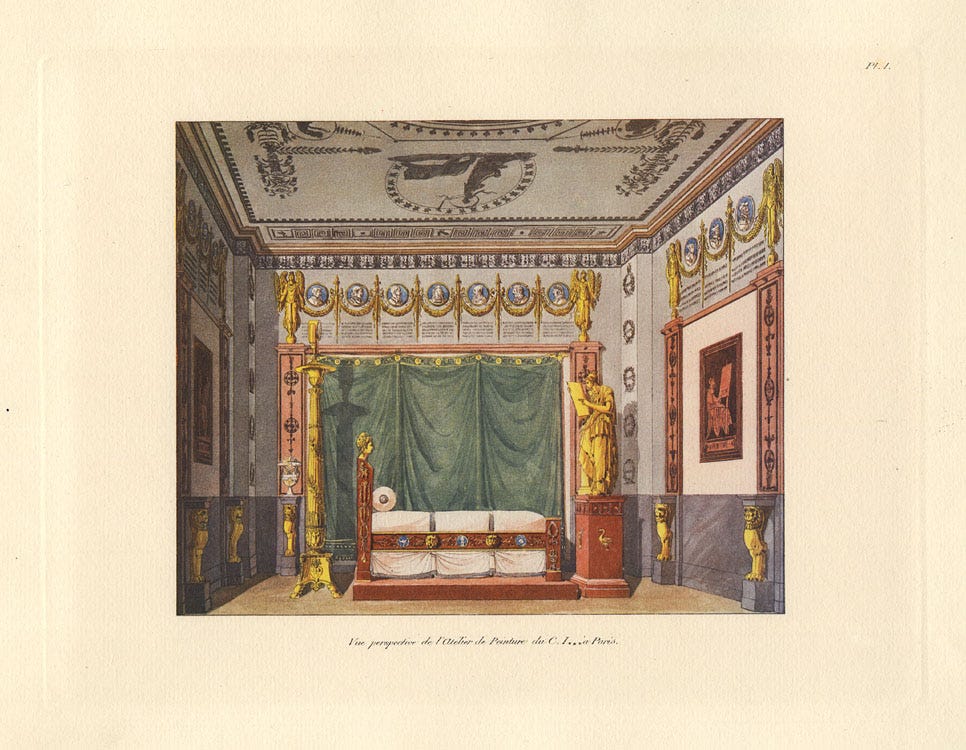

Design was an integral part of that authority. With the assistance of designers Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, Napoleon implemented what came to be known as the Empire Style. This was a grand but sober form of neoclassicism, with rigid lines and a large repertoire of motifs drawn from the ancient world: acanthus, palms leaves, wreaths and eagles from Greece and Rome; obelisks, pyramids, winged lions and caryatids from Egypt. Through this official style, whose most famous example is the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, Napoleon linked his regime to the timeless values of reason associated with classical civilisation.

But the Empire Style also portrayed this order as dynamic and expanding, drawing attention to the epic agency of its central figure. The Egyptian iconography recalled Napoleon’s expedition to the near east in 1798, which had sparked a fascination with Egypt in European fashion and intellectual life. More obvious still was the frequently used capital letter “N.” Blending the grandeur of the past with progress and celebrity, Napoleonic design showed a distinctly modern formula for authority, one that would be echoed by Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin more than a century later.

It also suggested the arrival of modernity in more concrete ways, as François Baudot has pointed out. The square proportions and functional character of its furniture, along with its catalogue of reproducible symbols, reflected the standardised methods used at France’s state workshop. As such, it anticipated the age of mass-production in the later 19th and 20th centuries. Large-scale production was needed, in part, to supply the burgeoning administration of the Napoleonic state: a state whose power derived not just from the court and army, but increasingly from bureaucracy too. “It proved a short step,” Baudot quips, “from the Empire desk to the empire of the desk.”

What feels especially familiar about the Empire Style is its ambition to create an aesthetic totality, a “brand identity” whose unity of style would encompass everything from the largest structure to the finest detail. It was, writes Baudot, “a style whose practitioners were equally adept at cutlery and facades, at the detailing of a frieze and of a chair, at the plan of a fortress and shape of a gown to be worn at court.” This concern for a fully designed environment brings to mind the fastidious approach of later styles like art nouveau and the moderne (when the Belgian designer Henry van de Velde conceived a house for himself in 1895, he produced not just matching cutlery and furnishings but a new wardrobe for his wife). It also anticipates the commercial designers of our time, hired to create an immersive aesthetic experience for a pop star or retail brand.

Admittedly the principle that power spoke with a distinct voice was not new, especially not in France, where Louis XIV had already overseen an extensive system of state workshops and artisans in the 17th century. Neoclassicism had been in vogue since the mid-18th century, and Napoleon’s version of it can be seen as a careful attempt to position his regime in relation to its predecessors. Without returning to the full opulence of the royal ancien régime, whose excesses had been repudiated in the revolutionary decade of the 1790s, the Empire Style was notably more grandiose than the republican Directory Style which came before it. Subtly but unmistakably, Napoleon was recalling the majesty of the Bourbons.

Nonetheless, the Empire Style did express real Enlightenment convictions. As Ruth Scurr details in her fascinating biography, A Life in Gardens and Shadows, Napoleon’s passion for neoclassical garden design reflected his deeply engrained rationalism and love of order. Right until his last days in exile on Saint Helena, where he diverted his frustration into horticulture, Napoleon liked gardens to display straight lines, precision and symmetry. These are the same characteristics that defined the Empire Style. In such apparently superficial details we see principles that would resonate through European history for centuries. Napoleon quarrelled with his first wife, Joséphine, over her preference for the more unruly and picturesque English style of garden. That English style was a portent of a very different response to modernity that would soon emerge in Britain, where aesthetic harmony was sought not in classical Reason but in the organic rootedness of the medieval Gothic.

Ultimately, what makes the Empire Style modern was the role it gave design in relation to society at large. Appropriately for an emperor who loved gardening, Napoleonic design reveals the emergence of what Zygmunt Bauman has called “the gardening state”: the modern regime that does not just aim to rule over its subjects, but seeks to transform society in pursuit of progress and even utopian perfection. The Empire Style communicated the ambition of the state – which, after the French Revolution, was meant to embody the nation and its citizens – to remake the world in the image of its ideals. But more than that, it showed a belief that design could be an active part of this project, its didactic powers helping to bring the state into being, and to instil it with an ideological purpose. Chairs and tables, buildings, interiors and monuments were not only intended to demonstrate reason and progress; they were intended to impart these values to the society where they appeared.

This entanglement with the modern progressive state or movement would continue to haunt design up until the ruptures of the mid-20th century. In the process, the aims of representing abstract ideals, securing the commitment of the masses and showing the promise of the future would turn out to be rife with contradictions. But we will have to leave all of that until next week.