X and the Race for the Super-App

Big tech rebrands are all about empire building

Twitter continues its metamorphosis. The company this week replaced its famous blue bird logo, a suitably childish symbol for a platform that turned us all into bickering infants, with a black and white “X”. As with the rebranding of Facebook as Meta a few years ago, the cuddly corporate kitsch of the 2000s has given way to something more muscular and enigmatic.

Many have assumed this is just a case of Twitter’s owner, Elon Musk, cocking his leg to mark his territory, and Musk does seem somewhat obsessed with the letter between W and Y. It has featured in the names of several of his companies and products, not to mention one of his children (who is called X Æ A-xii).

Yet both the Facebook/Meta and Twitter/X transitions reflect ideas about brand identity that go back to the 1950s and 60s. Those decades saw a boom in big multinational companies, as rapidly growing firms swallowed their rivals and moved into new markets across the world. This created a need for simple, versatile branding, which could unify sprawling operations with easily recognisable names and symbols. Paul Rand, who designed the iconic IBM logo in this period, believed in the “magical power” of letterforms, much as Musk seems to.

Big tech companies are likewise in a phase of expansion and integration today. Brands like Facebook and Twitter have been ditched because they are too narrow for the digital empires their owners are trying to build.

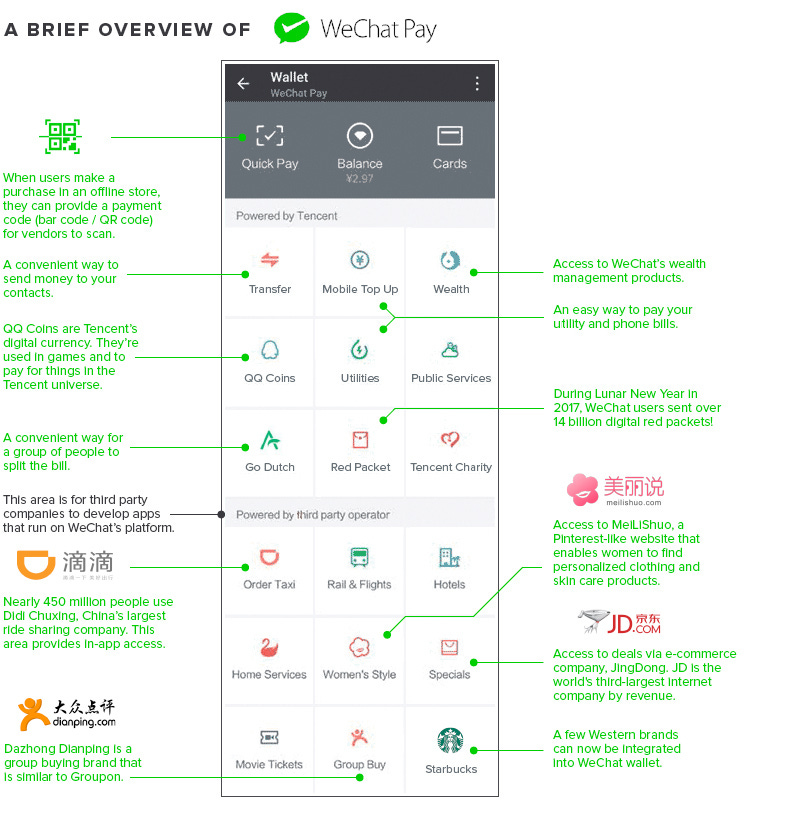

To understand these ambitions, we need to begin in China, where the tech industry has pioneered something its American counterpart is desperate to emulate: super-apps. As the name suggests, these are multiple platforms rolled into one. WeChat, the most successful example, combines a WhatsApp-like messaging platform with numerous other functions, including bill payments, transfers, online shopping, social media, gaming, dating and borrowing.

The appeal of this model to Silicon Valley is obvious. Tech companies want to maximise the time we spend on their platforms, as well as the range of things we rely on those platforms for. Having a large number of people ring-fenced in a digital “ecosystem” creates all sorts of opportunities for selling things to them, and for selling access to them. In particular, it allows companies to gather detailed personal data about their customers, which can be used for targeted advertising, and now for training AI systems as well.

Elon Musk has long hinted at his desire to create an integrated platform, especially for financial transactions. During the long saga of his Twitter purchase, when he talked about free speech and a building a “digital town square,” he was telling investors about his plans to introduce payments on the app. Last year he said to employees at the company, “You basically live on WeChat in China. If we can recreate that with Twitter, we’ll be a great success.”

So it’s little wonder that when CEO Linda Yaccarino announced Twitter’s rebrand on Sunday, her corporate jargon pointed squarely towards a super-app. “X is the future state of unlimited interactivity — centred in audio, video, messaging, payments/banking,” she wrote, “creating a global marketplace for ideas, goods, services, and opportunities.”

But there are other players in this race. PayPal and Uber are trying to expand across their local fields of finance and travel. Microsoft has reportedly considered developing its own super-app, and even Wallmart is moving into digital banking.

Then of course there is the artist formerly known as Facebook. When the company was renamed Meta, all the talk was about Mark Zuckerberg’s kooky visions of virtual reality, but the move had just as much to do with integrating his various properties – including WhatsApp, Instagram and now Threads – more closely under a single brand. In recent years new functions have been introduced to all of these platforms, notably ecommerce, payments and gaming.

As for Zuckerberg’s so-called metaverse, that too is simply a more ambitious expression of the same logic: a single, versatile operating system where users can do just about anything.

In the era of the “everything-app,” should it arrive, branding will try to occupy a new role in digital life. It will no longer be just a system of symbols and ideas that invite desire and familiarity. It will aim to become an almost feudal form of authority, an ambient principle that encompasses the lives of customers and oversees all their activities like a benevolent parent.

We already see this in the closest thing Silicon Valley has to WeChat, which is not actually an app, but Apple. That company’s spectacular success owes a lot to its strategy of locking customers into its ecosystem of gadgets and software. Once you have an iPhone, there is a good chance you will use Apple computers, Apple accessories, iCloud storage and Apple Pay, since the company makes these more convenient than the alternatives. Yet this is only possible thanks to the almost mystical appeal of the Apple brand, with its sleek, functional aesthetics that many people are happy to involve in every aspect of their lives.

In fact, the power of Apple is such that it may rule out the emergence of a genuine super-app in Western countries. It’s not clear that people really need one, when they already have everything more or less in one place on their smartphone. And since they’re used to having different apps for different functions, handing all of that responsibility to a single platform seems a little scary.

Given the extent of cultural and political polarisation today, it is difficult to imagine one brand charismatic enough to overcome that hesitation for everyone. If Elon Musk manages to bring his followers into the X universe, his opponents would avoid it, and probably seek their own super-platform. Society would then separate into digital pillars, each with its own news, banking and dating services. It would be similar to the arrangement in European countries like the Netherlands during the early-20th century, when different religious and political groups had parallel institutions.

In that eventuality, brand imagery will reach its natural endpoint as the identity markers of new tribes.