Why I'm scared of the YIMBYs

To build well, we need greater ambition; but that means greater risk.

Should we build a city for a million people in the Cambridgeshire and Suffolk countryside, surrounded by 12,000 acres of woodland? This project is being seriously proposed by businessmen-turned-campaigners Shiv Malik and Joseph Reeve. It is a crazy idea, and seems unlikely to be realised. Yet in many ways it represents a step forward in the vexed debate around building and development in Britain, something that only a crazy idea could achieve.

For starters, it is good to see Reeve acknowledge that Britain’s housing shortage is not the fault of NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard, i.e., people who block local developments for unreasonable and selfish motives). The war on NIMBYs inspires such passion that people who want more building now call themselves – you guessed it – YIMBYs. In reality, this grudge has long since become a way of blaming those who take pride in their local area for the failings of, inter alia, developers, house builders and local authorities. As Reeve explains, the objections of “concerned locals” to new housing typically include:

o “The houses are ugly.” (They are.)

o “The roads can’t cope.” (They can’t.)

o “It’ll be a soulless commuter estate.” (It will.)

o “The ‘affordable’ homes cost £900,000.” (They do.)

Reeve continues: “These objections are not irrational. They are accurate observations about British housebuilding, which has spent fifty years optimising for ‘maximum profit per acre’ and ‘aesthetic qualities of a cardboard box.’”

Reeve made a similar point last year at an event hosted by Looking For Growth, a movement seeking to reverse Britain’s economic decline (I reported on the LFG event here). Apparently he realised the wisdom of building a new city when driving through a rural area and seeing “shitty houses” going up “in the middle of nowhere”. He and Malik insist that the best way to spare the countryside, enforce better design standards, and boost economic productivity is to concentrate development in new urban settlements, built from scratch. Prices will allegedly by kept down through an innovative “community land trust” model, while environmental damage will be offset by doing something significant for nature regeneration at the same time; hence the forest.

What is significant here is the attempt to break the deadlock between conserving versus building, by taking greater responsibility for both. Along with their hatred of NIMBYs, the YIMBYs have spent too much energy complaining about the rules and regulations, especially regarding the environment, which have reduced Britain to a state of paralysis. They are not actually wrong; it is true that a monumental accretion of rules and bureaucratic structures have gummed up the economy and made life miserable for anyone who wants to make, build, or organise something. But there is another side to this problem. Despite all the regulation, we are still failing to protect our landscapes, waterways and wild animals. Britain is one of the world’s most nature-depleted countries, with almost one sixth of species classed as threatened with extinction. As for the countryside, it looks big in statistical terms, but the reality for those who live there often amounts to protecting small pockets of rural peace from ever-encroaching towns and traffic.

In other words, when it comes to matters of conservation and development, we are close to a worst-of-both-worlds situation. That is, we are failing at both. So if one constantly denounces regulation without addressing the double-edged nature of the problem, there comes a point where one is effectively sweeping the environmental issue under the carpet. See, for instance, the recent controversy surrounding the so-called “fish disco” at the Hinkley Point C nuclear plant in Somerset. This is not, sadly, a place for fish to dance, but a system of underwater speakers meant to keep them at a safe distance. When a government review suggested that the fish disco cost £700 million and would not actually save any fish, YIMBYs saw yet another symbol of costly and pointless bureaucracy, an environmental absurdity to rank alongside the infamous bat tunnel and various scandals involving newts. But it now transpires that the £700 million covers a suite of protective measures, and early trials suggest the fish disco actually works.

More importantly, even if the fish disco did deserve to be ridiculed, I didn’t see its detractors acknowledge that marine wildlife is worth protecting. And yet, around the same time, researchers in neighbouring Dorset reported that the numbers of salmon in the rivers are now the lowest on record. Salmon populations have been falling rapidly across Britain, as the Times reported: “Numbers of wild Atlantic salmon have crashed by about 80 per cent in the past 40 years. Rivers that had tens of thousands of salmon in the 1980s now only have a few hundred.”

Again, I am not denying that intrusive and burdensome regulation is a problem. But it doesn’t change the reality that we are failing to protect things which ought to be protected. As I say, a worst-of-both-worlds situation. Britain is now a country where individuals are fined for dropping cigarette butts or pouring coffee down drains, while rapacious water companies are endlessly pumping raw sewage into the rivers, and fly-tippers dump lorry-loads of rubbish into the countryside. A country where eye-watering energy bills are inflated to pay for green policies and refurbishing a home can entail painful rigmarole, even as once plentiful insects and birds are vanishing along with the habitats that support them.

To make matters worse, even if we had highly efficient regulators, they would still face an extremely difficult task. Consider the fish again. The factors destroying the wild salmon population are complex and various. Rivers and streams are becoming too warm, reflecting climactic change but also the legacy of Victorian landscaping practices. Oxygen is being sucked out of waterways by vast algal blooms, fed by nitrates from sewage spills and agricultural fertilisers. Meanwhile at sea, where wild salmon spend the majority of their lives, they catch diseases from the farmed salmon we buy in the supermarket. They also fall prey to fishing nets, and suffer from the collapse of marine food chains through overfishing. The scope of such challenges means that addressing them probably will require some expensive and elaborate contrivances like underwater acoustic deterrents (as fish discos are formally known). It also means that it will be very difficult to stop even well-intentioned regulators from spreading their tentacles everywhere.

I’m sure there are YIMBYs who see this mess and conclude that conservation simply isn’t worth the trouble. But could they win political support for a program of BUILD BABY BUILD (to quote the MAGA-style baseball cap worn by Labour housing minister Steve Reed)? I suspect there is more appetite for “cutting the green crap” than someone like me would like to imagine, but probably less than the YIMBYs would hope. Surveys by More In Common suggest that just one in five people think that weakening environmental standards is worthwhile for more house building, and also, remarkably, that 73% cite proximity to the countryside as important when looking for a home, which is more than prioritise being near a good school. These findings cut both ways, of course: if everyone who wants to live near the countryside actually did, there would be no countryside left. Still, there is reason to think that some city dwellers feel protective towards the natural and rural worlds, if only to preserve something outside the urban condition that threatens to swallow the vast majority of humanity.

The question then is how, given all these difficulties, we can move towards a best-of-both-worlds scenario. There are some obvious steps. We could, for instance, build a sanitation system to match a ballooning population, so that sewage isn’t dumped in rivers and on beaches. We could encourage more domestic manufacturing, so that we don’t need to import everything from countries with much lower environmental standards. We could create more homes in cities like London, where house building has fallen to a record low. But let’s push the boat out a little further, to acknowledge the depth of the dilemma. What would the best-of-both-worlds actually look like?

It would, presumably, demand a meticulous planning regime to distribute space between urban, rural and natural settings. It would require massive investment in nature conservation and regeneration, as well as in abundant, state-of-the-art infrastructure. It would involve new buildings of such quality and beauty, situated so sensitively in their environment, that local people would be happy to have them. It seems we have entered the realm of science fiction. To find the perfect balance between development and conservation, we will need a benign dictatorship of artist-engineers, flush with money and unbothered by existing political institutions or property rights, able to move populations and demolish and build settlements as their immaculate judgment required.

The point of this silly thought experiment is to illustrate that, if we want to get even one-tenth of the way to the best-of-both-worlds scenario, we will probably need some ambition and creativity. This is why I say the Forest City proposal marks a step forward in the debate. However flawed the project might be, it is not suggesting, as much YIMBY discourse seems to, that we can go back to the unchecked building sprees of earlier generations, the effects of which are precisely what created scepticism to further development. Malik and Reeve appear to recognise that developing our built environment must somehow be part of the same project as regenerating our natural and rural ones, and that this, in turn, will require a paradigm shift in vision and ambition. This is part, I think, of a wider High Modernist tendency emerging within YIMBY thought. Another example is Anglofuturism, a playful concept that tries to reconcile cultural heritage with technological change, toying with ideas such as “a spacefaring Britain building Georgian townhouses on the Moon, [and] small modular reactors delivering nuclear energy from underneath village greens.”

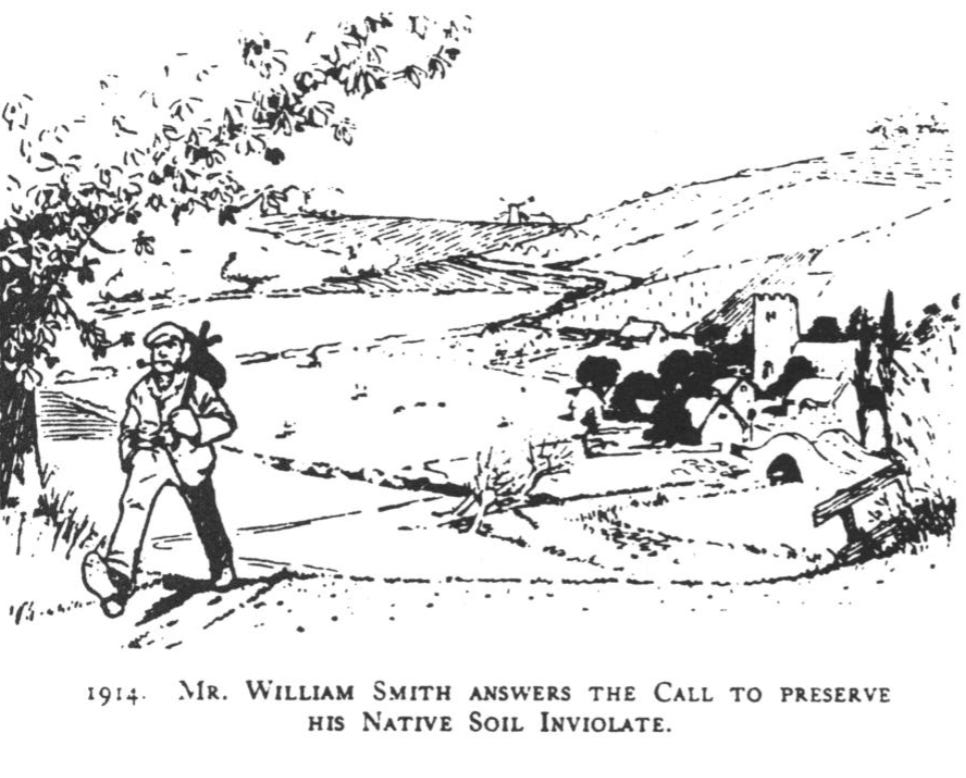

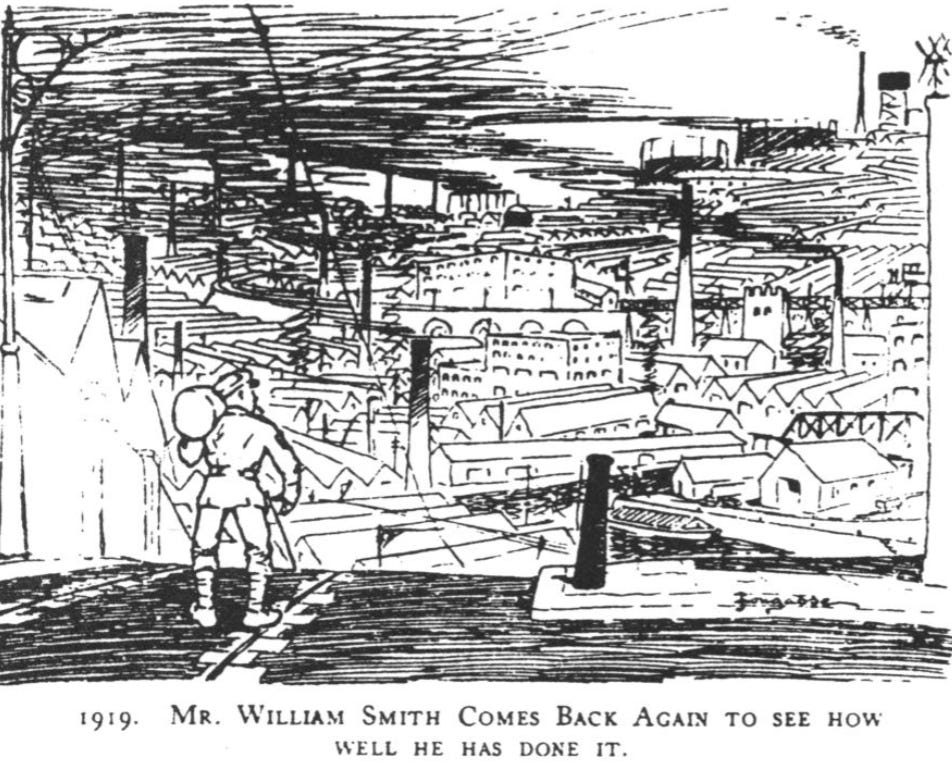

The problem with greater ambition, of course, is that it brings greater risk; and this raises major political obstacles. A bold, transformative vision may be effective at winning support in general terms, because everyone likes uplifting rhetoric, but it becomes frightening once specific projects and policies are on the table. The general mood in Britain today seems to be unhappiness with the status quo combined with fear that change will only make things worse. It is easy to say that the buildings will be beautiful and affordable, that the neighbourhoods will be lively and nature will be enhanced, but such promises are par for the course from property developers. Why should anyone believe that this time will be different? Once a Bristol-sized chunk of countryside is handed over to build a city, it will never come back.

Thinking big, devising new ways to pursue stewardship alongside development, is the only way to create a prosperous modern society without destroying the natural and cultural wealth that future generations ought to inherit. But we lack the trust, and probably the means, to get such schemes off the ground. Housing estates will continue to be shoehorned piecemeal into villages and fields because, ultimately, it is easier to stitch up a local community than to convince entire regions to take a leap into the dark.