The Spaceship as Political Symbol

Science and technology have long been matters of national pride

Last week, after India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft touched down near the south pole of the moon, a BBC news clip went viral on social media. Could India really afford a space program, the presenter asked rather obnoxiously, when the country “lacks a lot of infrastructure,” and “more than 700 million Indians don’t have access to a toilet?”

It turns out the clip was actually from 2019, when India launched its previous, ultimately unsuccessful attempt at a moon landing. Nonetheless, the incident is notable for the outraged response to the BBC presenter’s question. Many Indians claimed the Brits were simply jealous of their achievement; others politely suggested the broadcaster mind its own business.

One should never assume that angry people on the internet are representative of any wider sentiment, but the euphoric scenes that greeted the success of Chandrayaan-3 – the first lander to reach this lunar region in one piece – indicate a significant moment for the nation. Screenings were organised in schools across the country, flag-waving crowds streamed through New Delhi, and the national cricket team was photographed watching the landing in pitch-side tent.

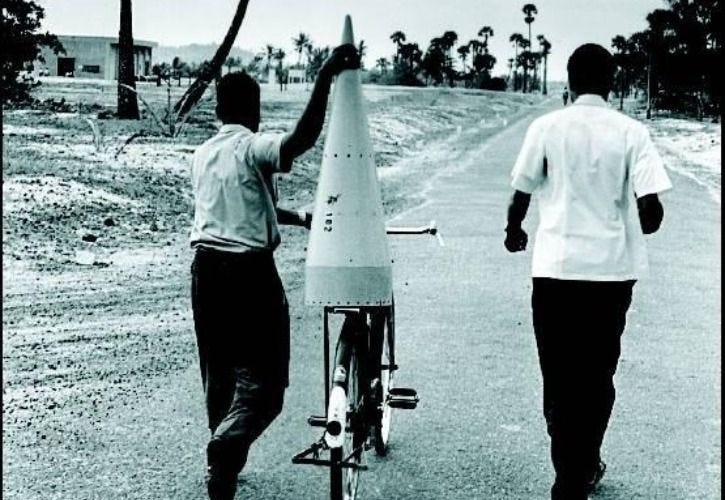

Nor is this surprising, given India’s remarkable commitment to science and technology since independence. In 1963, the tip of the country’s first rocket was famously transported to its launchpad with a bicycle. When Indian nuclear tests provoked sanctions from the United States in the 1970s, the technology sector was forced to adopt a culture of self-reliance and resourcefulness. It has become a point of pride that Indian space programs have lower budgets than many Hollywood films (another common riposte to that sceptical BBC presenter).

The legacy of that commitment is visible today in India’s thriving tech industries, and in the extraordinary success of the Indianian diaspora. In 2012, Forbes reported that Indians had founded 14% of Silicon Valley start-ups. Men and women of Indian descent are or have recently been CEOs of Microsoft, Alphabet, IBM, Twitter and Adobe, to name just a few. Many of these individuals are graduates of India’s state-funded technology institutes, or of its numerous engineering schools.

But the impassioned reaction to the BBC clip hints at something deeper: the political power of technological achievement. The outrage seemed to stem from a sense of profanity, from indignation that someone could discuss the provision of toilets in the same sentence as a heroic feat of discovery. Do some things not have a significance that transcends material concerns? The billionaire Anand Mahindra articulated as much when he claimed that space exploration was especially important for a nation robbed of its self-worth by colonial subjugation. “What going to the moon does for us,” Mahindra wrote, “is that it helps restore our pride & self confidence. It creates belief in progress through science. It gives us the aspiration to lift ourselves out of poverty.”

This sense of an endeavour that transcends the mundane and material – an endeavour of pride, progress and aspiration, in Mahindra’s words – can breathe life into a political community. It makes individuals feel part of some larger project that is imbued with purpose, and grants them a share in the achievements. Technology and scientific discovery are especially well suited to this kind of project, since they demonstrate worldly power and movement towards new horizons. Space exploration combines both.

All this was evident during the original Space Age, which played out against the backdrop of the Cold War. In both the Soviet Union and the United States, governments recognised that space programs could be a means of harnessing popular enthusiasm and garnering legitimacy. The Soviet regime celebrated its breakthroughs of the 1950s and 60s with public rallies, lectures, and laudatory works of literature and music. In the United States, television broadcasts of the Apollo missions were among the prominent media events of the 1960s.

Both cultures had an existing fascination with the science-fictional realm of space and space technologies. But the context of the Cold War, in which technological superiority seemed so important, helped to make extra-terrestrial exploits a matter of national standing and pride. “Arrogant Western theoreticians predicted that bast-shoed Russians would never become a great power,” declared Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in 1961, after Yuri Gagarin became the first person to enter orbit. A few years earlier, the U.S. government had been forced to ramp up its own space ambitions when the first Soviet satellite, Sputnik 1, sparked panic in America.

The Space Age did, in fact, see plenty of complaints about financial priorities. When the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission launched in 1969, protestors organised by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference gathered at the Kennedy Space Center with mules and a wagon, illustrating the plight of the poor in America. As Howard McCurdy notes, fifty-eight percent of respondents to a 1960 Gallup poll said the U.S. should not spend $40 billion “to send a man to the moon.” There was less scope for debate in the Soviet Union, but writers there likewise questioned the wisdom of diverting resources to rocket launches and satellites.

Indeed, displays of technological prowess do not magically heal the fractures in a society. And yet, while people may claim that such projects are a waste of money, this does not make them immune to the resulting feelings of collective prestige. This emotional power occupies a different plane from economic reasoning. Americans persistently opposed funding for space missions right through to the 1980s, but they just as persistently expected them to take place. Or as McCurdy puts it: “the number of people who wanted to undertake these projects exceeded by a factor of two the number of people willing to increase the space budget to pay for them.” Surveys from the 1960s suggest that Americans regarded the Space Department as a highly competent organisation, a view that surely contributed to the record levels of confidence in government during this period.

I’m by no means an expert on India, but it appears that technological ambition is similarly entangled with questions of national pride and identity there. Prime minister Modi’s aggressive promotion of technology, through initiatives such as Make in India and Digital India, belongs to a wider agenda of Indian greatness. On a recent visit to the United States, Modi secured American partnership in a range of hi-tech ventures, including space exploration, fighter jet engines and semiconductors. This is part of his effort to position India as a major global player, balancing between China, Russia and the U.S.

Meanwhile, as Arun Mohan Sukumar has observed, technology also has peculiar significance for Modi’s domestic project of Hindu nationalism, a distinct brand of modernity infused with religious identity. This is perhaps most evident in the rise of a discourse attributing modern technical achievements to ancient Hindu civilisation.

All of this poses interesting questions about the private space adventures funded by American billionaires such as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. Here it is difficult to see how anger over misspent resources could be balanced by the warm glow of shared achievement, since Musk and Bezos do not act on behalf of any political project. Ironically, it is the grandiose universalism of their visions, claiming to represent the future of humanity as such, which allows critics to portray them as nothing but selfish megalomaniacs. If everyone can feel pride in their achievements, then no-one will.

Yet the Chandrayaan-3 mission is a reminder that private space companies will not be stealing the headlines for long. We are now on the cusp of a new space race. Both the United States and China are hoping to establish permanent bases on the moon by the 2030s, and thereafter to send manned missions to Mars. If the past is any guide, these will not just be scientific endeavours, but political theatre too.