The Meaning of Lady Gaga's Fingernail

Our enduring belief that people can be present in objects

Every now and then I come across a news story about the auctioning of a famous person’s belongings. In August, a cigar stubbed out by Winston Churchill in 1963 found its way to an admiring bidder, and last year, Steve Jobs’ well-worn and mouldy-looking Birkenstocks fetched over $200k. I recently read about a Parisian businessman who spent the 1990s collecting outfits that Prince had worn on stage; no shortage of those, it turns out, since the singer employed dozens of people to churn out garments for his extravagant wardrobe.

I started to get curious about this traffic in celebrity relics. What exactly are fans willing to buy? The answer is virtually anything: dresses and shoes, musical instruments and furniture, discarded chewing gum and half-eaten pieces of toast, the underwear of an American president and of two British queens. That’s not to mention the items that were actually part of a famous person’s body, like Justin Bieber’s teenage hair, John Lennon’s tooth, or Lady Gaga’s acrylic fingernail.

For all its weirdness, this trade illustrates some profound aspects of our relationship with objects. It is a reminder that even the most mundane items can be infused with sacred significance, and that design is sometimes responsible for very little of the ultimate value and meaning of a product. It shows, moreover, that even something as modern as celebrity culture exists partly as an outlet for ancient tendencies, apparently innate to the human psyche.

Why do people buy these things? Sometimes just for a laugh I suppose. But there is enough truth in the phrase “celebrity worship” to assume that many of these collectors are engaging in a sincere form of obsession. The history of relics (that is, sacred remnants) spans countless cultures and epochs, and amply demonstrates our ability to treat objects as substitutes for special people – to see material things as though they are imbued with the spirit of a particular individual. Relics are most familiar from the Christian context – in medieval Europe, every altar was expected to contain one – but we shouldn’t assume they are alien to modernity.

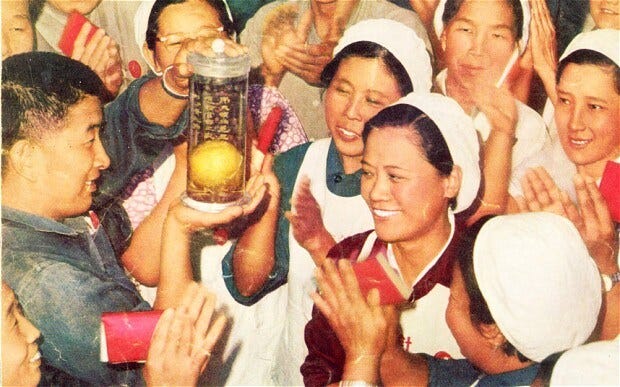

Consider the strange case of Maoist China’s Mango Cult. In 1968, when China was in the throes of its Cultural Revolution (a movement that violently suppressed traditional religion, among other things), the Communist leader Mao Zedong received a box of mangoes from the Pakistani foreign minister. He passed the fruit on to a group of loyal factory workers, who did not consume them but tried to preserve them by various means. The mangoes rapidly became sacred objects representing Mao. They were displayed around the country, honoured in processions, copied in wax and celebrated in posters and poems. At least one man was ritually humiliated and then executed for disrespecting these tropical relics, having compared a touring mango with a sweet potato.

The anthropologist Adam Yuet Chau observes that “not only was the mango a gift from the Chairman [Mao], it was the Chairman.” Likewise, today’s celebrity relics seem desirable insofar as they show traces of the revered individual’s presence, as with the tooth-marks on Churchill’s cigar, or the worn soles of Steve Jobs’ sandals. This recalls holy items like the Turin Shroud and St Veronica’s veil, cloths which are said to bear Christ’s image after contact with his body. Alternatively, the famous can be conjured by the accessories and instruments which symbolise their persona: Andy Warhol’s silver wig, or John Lennon’s round sunglasses.

No doubt some collectors are more interested in the status such trophies confer on them, but that, too, implies a belief that the object somehow captures the aura of its famous owner.

One quality that sets celebrity relics apart is the absolute importance of their authenticity. Millions of Catholics venerate the Turin Shroud despite doubts over its origins (even the Vatican does not insist it is real), and Mao’s supporters did not hesitate to mass-produce plastic mangos for worship. The case seems to be rather different with Scarlett Johansson’s used tissue, or Kurt Cobain’s cardigan. If these things turned out to be fakes, their banality would reassert itself instantly. What we are glimpsing here is the difference that social identity makes. As I’ve argued in the past, charisma does not necessarily come from personality; it can be projected onto a leader by his or her followers, as a way of cementing their own bonds. I think the same goes for charismatic objects: if they provide a focal point for collective reverence, it doesn’t matter if they are authentic or unique.

In other words – and with the possible exception of K-Pop – celebrity worship still lacks the unifying force of organised religion and politics; that is why its relics are collector’s items traded at auction, not communal treasures. Then again, the fact that someone would pay $13,000 for a pop star’s fingernail does not suggest any shortage of devotion.

In 2002, a resident on campus bought Chas Tenenbaum's red tracksuit on eBay for a large amount. He always wore it. My friends said he was very creepy, and having met him, saw it gave him a source of pride, something he didn't have much of at the time. I think a lot can be learned from artifacts, but some prefer to be a walking museum.

The Mao Zedong Mango Cult made me laugh. The price people are willing to pay for that sense of a personal connection never ceases to amaze.