The Lost Magic Of The Seas

Seafaring cultures made the modern world – and then disappeared

Many British people will hear about Felixstowe for the first time this month, thanks to a planned workers’ strike that promises yet more economic pain. Located on the Suffolk coast, Felixstowe is the site of the UK’s biggest container port; almost half of the goods coming and going from our shores pass through here, stowed away in brightly coloured shipping containers that resemble enormous Lego bricks.

The absence of Felixstowe from the national vocabulary speaks volumes about the era we live in. Britain is an island after all, and its various port towns have been central to its history for centuries. Now we are more dependent on the sea than ever (around ninety percent of the world’s traded goods travel by ship), but we barely realise it.

So what happened? That is the question I want to consider today, with the help of David Abulafia’s The Boundless Sea, an epic history of human activity on the ocean. One of the themes in this book is the relationship between the intimate and the global: how our sense of what is valuable or important is tied up with our impressions of the world at large.

Container ports appear in the final, slim section of The Boundless Sea, where Abulafia describes the disappearance, since the 1950s, of the ancient maritime patterns he has detailed for some 900 pages. “By the beginning of the 21st century,” he writes, “the ocean world of the last four millennia had ceased to exist.”

Given the dramatic nature of this change – a mass extinction of seafaring cultures around the world – the treatment is strikingly brief. Then again, this is a useful reminder that modernity is a tiny slice of time containing enormous transformations.

Container ports symbolise this rupture from the past: mechanised coastal nodes where huge vessels, each bearing thousands of standardised containers, load and unload goods from around the world. By contrast to the lively port towns that litter The Boundless Sea, container ports “are not centres of trade inhabited by a colourful variety of people from many backgrounds, but processing plants in which machinery, not men, do the heavy work and no one sees the cargoes… sealed inside their big boxes.” Felixstowe, says Abulafia, is “a great machine.”

Who crossed the oceans before the container ships did? Polynesian navigators explored the vastness of the Pacific over millennia, with only the stars for a compass. Bronze Age Egyptians ventured down the Red Sea in search of frankincense and myrrh. Merchants in sewn-plank boats spread Buddhism and Islam in the southern Indian Ocean, even as Vikings set out from their Greenland farmsteads in search of narwhal tusks. In the early modern era, pirates, traders and profit-hungry explorers swarmed the coasts of Africa and the Americas. These examples are just a drop in the ocean of Abulafia’s sweeping narrative.

But despite its enormous scope, there is a golden thread running through this book, uniting different eras and pulling continents together: the human desire for rare, beautiful, and exceptionally useful things.

The main protagonists of maritime history are merchants, since buying and selling has been the most common reason to cross the seas. But what is difficult to grasp today, when even the most mundane products have supply lines spanning the oceans, is the special value which has often been attached to seaborne goods, especially before the 18th century. Some cities, most famously Rome, did rely on short-distance shipping for basic needs like food. And some products, like English wool or Chinese ceramics, were crossing the water in large volumes centuries ago. But generally the risks and expenses of taking to sea, especially over large distances, demanded that merchants focus on the most sought-after goods. And conversely, goods were particularly precious if they could only be delivered by ship.

So seaborne cargoes show us what was considered valuable in the places they docked, or at least among the elites of those places. The human history of the oceans is in large part a catalogue of highly prized things: ornate weapons and exotic animals, spices and textiles, materials like sandalwood and ivory, or foodstuffs like honey, oil and figs. Of course that catalogue also includes human beings reduced to the status of objects, such as eunuchs, performers and slaves.

If the value of such things was generally financial for merchants, it took many forms in the cultures where they arrived. Before the ocean could be reliably traversed with steamships and (eventually) aeroplanes, foreign products bore the mystery of unknown lands. They often became tokens of social status, symbols of spiritual significance, or preferred forms of sensual pleasure and beauty. Ivory from African elephants and north-Atlantic walruses were treasured materials for religious sculpture in medieval Europe, just as red Portuguese cloth was prized by West African elites in the 17th century.

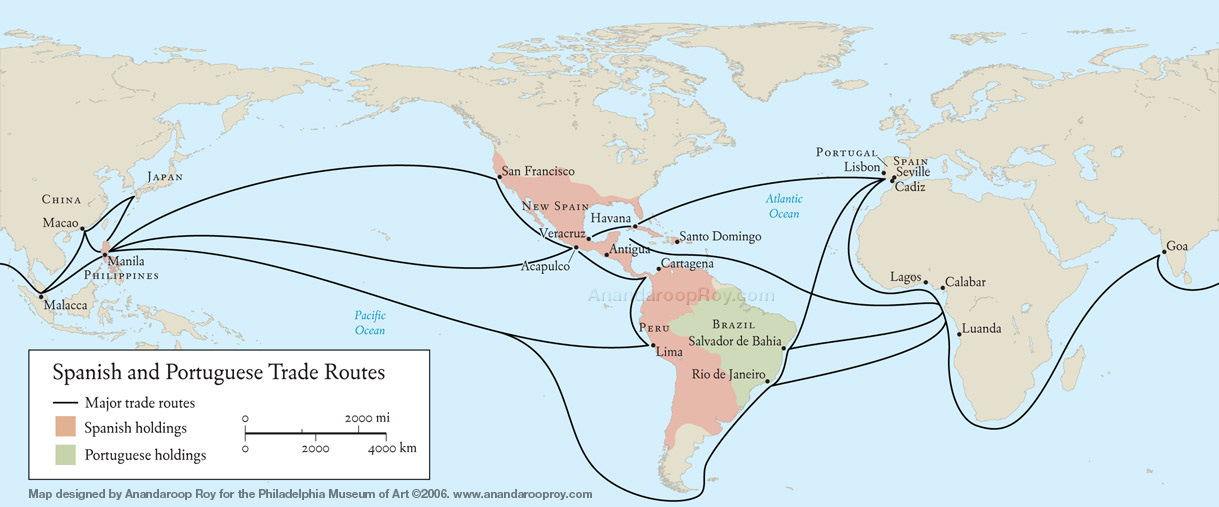

This traffic in desirable objects made the world we know today. The European expansion that began in the late-15th century was driven by the prospect of delivering expensive goods in ever-larger quantities, making them accessible to an ever-larger market. These included products only available in East Asia, like silk, spices and high-quality ceramics, and those that could only be produced with slave labour in tropical climates, such as sugar, coffee and tobacco.

Once the Spanish had established a Pacific route between the Americas and the Philippines, the first truly global networks appeared. The volume of maritime trade began to grow, and one of the foundations of modern capitalism was in place. Abulafia aptly describes Chinese junks arriving in Spanish Manila as “the 16th century equivalent of a floating department store.” Among the items in their holds were “linen and cotton cloth, hangings, coverlets, tapestries, metal goods including copper kettles, gunpowder, wheat flower, fresh and preserved fruits, decorated writing cases, gilded benches, live birds and pack animals.”

But no less dramatic than the growing movement of goods, people and ideas was the emergence, for the first time, of a global consciousness. This is strikingly visualised by the maps that accompany each of the fifty-one chapters of The Boundless Sea. In the first half of the book, these maps show the relatively small regions in which maritime connections existed, with the exception of the world’s oldest trans-oceanic network in the Indian Ocean. In the second half, the maps zoom dizzyingly outwards, eventually incorporating the entire world.

That world map is something we take for granted in an era of instant communication and accessible satellite imagery, but for most of history, huge swathes of the globe were completely unknown to any given group of people. To be fully aware of our species’ planetary parameters marks nothing less than a revolution in how human beings understand themselves. And one of the driving forces behind that revolution was the ambition to bring desirable (and profitable) things from across the ocean.

But if trade underpinned seafaring ways of life throughout history, it finally led to their extinction. More and more shipping did not just make formerly exotic goods commonplace, it eventually made most states integrate their economies into a global marketplace, so that seafaring became more like a conveyor belt than a culture. This culminated in the container ships that now have the oceans almost to themselves, their efficiencies of scale rendering other forms of seaborne trade obsolete.

In the age of the container, most products do not even come from a particular place. They are devised, extracted, processed, manufactured and assembled in many different places, so as to achieve the lowest cost. Even things that do come from distant lands no longer have the same aura of the unfamiliar, since the world is now almost entirely visible through imagery and media.

And that is where this story provides an important insight into the way we design, exchange and value objects today. In consumer societies, enormous resources are devoted to engineering desire, by making products appear uncommon and exclusive. We are used to thinking of this practice as peculiarly modern, and in many ways it is. But maybe we should also see it as an attempt to recreate something of the lost value that, for most of human history, belonged to things from across the ocean.