The Digital Doppelgänger

Deepfake technology is terrifying, but it could also be liberating

Fraud is an ugly business, but sometimes it can resemble a kind of cultural critique. This week the actor Russell Crowe became the latest celebrity to have his voice and appearance “deepfaked” – that is, replicated by software – for the purpose of flogging a product. On social media, Crowe warned of a bogus video where a grainy, robotic-sounding version of himself appears promoting a property app in Malta. This comes after a fake Tom Hanks popped up selling a dental plan, and a fake Taylor Swift took part in a scam involving Le Creuset cookware sets. It’s as though the fraudsters are mocking the grubby reality of celebrity culture, where stars treat their faces as monetisable assets and fans will buy something just because a celebrity has told them to.

But the spread of deepfakery is no laughing matter. This technology is maturing just as we are entering the biggest election year in history, with more than half the world’s population eligible to cast a vote in 2024 (though many of these elections are themselves far from honest). The forged audio of Joe Biden that was circulating this week, in which the U.S. president told his voters not to participate in the New Hampshire primary elections, surely won’t be the last of its kind. Still more disturbing is the increasingly widespread use of deepfakes for porn. One case last year involved photographs of more than twenty Spanish teenage girls, taken from Instagram and doctored to make them appear naked. The apps that produce these images are already widely accessible; we are entering a world where anyone (and they will mostly be women of course) can be instantly and realistically rendered as a pornographic object.

Understandably, such hideous exploitation is the greatest cause of concern about deepfakes, but we ought to consider the broader cultural and emotional implications too. As artificial intelligence is incorporated into smartphones, it is becoming possible for anyone to “edit photos to a degree never seen before, exchanging sad faces for happy ones and overcast afternoons for perfect sunsets.” We will soon reach a situation where every image, video and audio claiming to represent a real person will be suspect. In the seventeenth century, it was people not believing the evidence of their senses – thanks to the strange new phenomena revealed by telescopes and microscopes – that catalysed the emergence of modern science and philosophy, leading to a radically different way of seeing the world. Most famously, Descartes questioned how he could know that objective reality was not really an illusion fostered by an evil demon. The era of digital replicants, fabricated by the demonic powers of AI, may have similarly profound ramifications.

The stakes are high because we have never invested as much significance in images of ourselves as we do today. We may not reap the financial rewards of Tom Hanks or Taylor Swift, but social media encourages us to take a similar view of our public persona as an asset to be carefully managed. This already involves a kind of artificial duplication, but one that we control. Our virtual self is an external object that we shape and curate, but which we continue to identify with, feeling pride or shame on its behalf. This model can’t survive in a world haunted by deepfakes. We will no longer have exclusive control over what we are represented as doing or saying, and our audience may question whether it is really us they are seeing.

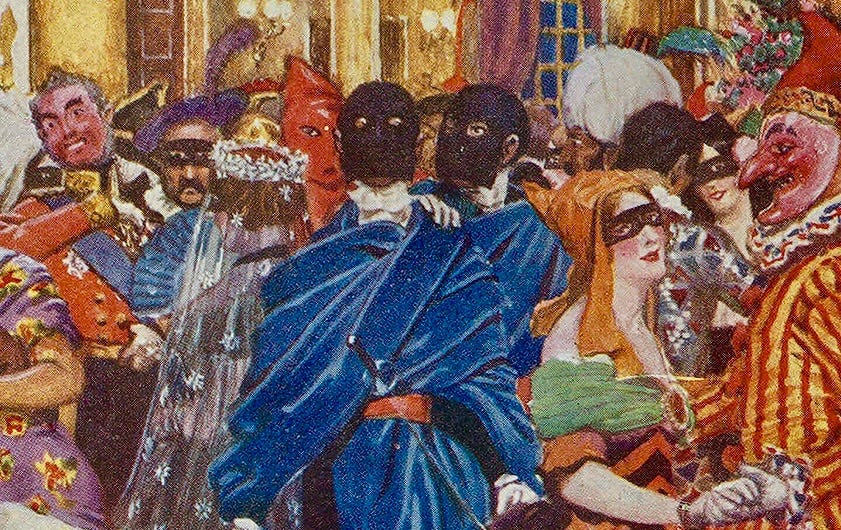

Maybe in the near future, we will know that at any moment we could be confronted with an unfamiliar version of ourselves, an “I” with a life of its own, simultaneously us and not us. In a sense this recalls the doppelgängers of gothic literature, except that those uncanny doubles generally symbolised some conflict within the individual. In Edgar Allen Poe’s wonderfully spooky story “William Wilson,” the doppelgänger seems to represent the conscience, and in Jekyll and Hyde, it suggests the violent impulses that lurk inside us. Deepfakes, by contrast, point to a different kind of struggle for identity between the individual and the world; they will force us to confront what others, quite literally, make of us.

These possibilities reflect deeper shifts happening in tech capitalism. The pressure to project our image into public was part of the creator economy, which cast each of us as a personal brand producing the intellectual property we call “content.” Generative AI cuts squarely against that paradigm. Not only does it displace us as content creators, it does so by harvesting and “digesting” our intellectual property on an enormous scale to train its algorithms. Those algorithms can then do things like produce deepfakes. So losing control of our faces and voices is just one striking sign that human beings are no longer the main actors on the digital stage, if indeed they ever were.

This could, however, bring some unexpected benefits. Last week I wrote about the problem with the ideal of authenticity, which stifles us with the expectation that we should bare our identity to the world. If deepfakes force us to emotionally distance ourselves from our public image, the result could be more playful and expressive ways of presenting the self, free from the burden of displaying our “real” personality. That intimacy would be reserved for real-world interactions where we are physically present – a presence that can’t be counterfeited. In the most extreme case, if we don’t stop this technology being used to make depraved and humiliating images, people will withdraw their appearance from public space altogether.

Nicely done, Wessie. I'll try to respond in more depth, but this is one place to start thinking seriously about digital outputs (texts, images, music) as representations. There is a lot that now old fashioned literary theory has to teach about how, and how not, to take digital media seriously. More anon. Keep up the good work!