Parenting as a Craft

What have I embarked on?

I recently saw a friend for the first time since becoming a father this summer past. “How are you finding it?” he asked. I spent a few moments thinking how to respond, and realised I was getting nowhere. My lips opened in readiness for speech, but no speech was forthcoming. Where to begin? Did I even know the answer to his question? Fortunately he has had children much longer than I have, and understood my silence perfectly well.

If I had to put words into that silence now, I would say this. Having a small infant around is a delightfully strange, enthralling, often hilarious experience. It’s hard work, yes. But the real difficulty, for me, is trying to understand what exactly I have embarked on. When I think that I have to raise this creature – this unspeakably precious creature – into a child, an adolescent, and ultimately an adult, I am baffled that the cosmos has entrusted me with such a responsibility. Never have I felt so conscious of my shortcomings, so unworthy of a privilege.

This is when I take heart from the fact that feelings of inadequacy are common to many kinds of beginning. Every new skill or ability, every career and every art is a quest that starts with a punishing encounter with one’s limitations. When learning to play a musical instrument, your fingers initially cannot even perform the necessary movements, just as, when learning a language, you cannot form or even hear the sounds properly. The distance between such tentative beginnings and the goal of mastery is absurdly large, and yet people reach it all the time.

There are a few problems with this analogy – you won’t receive a visit from social services if you neglect your violin practice – but as a new parent, I find it helpful to think of my situation in these terms. As Richard Sennett argues in his book The Craftsman, parenting can be understood as a craft, meaning an activity in which knowledge, skill, technique, and improvement are possible. One does not have to rely on some innate talent that may or may not appear. “Craftwork,” writes Sennett, “focuses on objects in themselves and on impersonal practices; craftwork depends on curiosity, it tempers obsession; craftwork turns the craftsman outward.” In its social and moral dimensions, this vision of craft resembles the concept of a practice.

Sennett traces this approach to parenting back to the eighteenth century Enlightenment, with its boom in printed material seeking to spread knowledge to a wide audience. Hundreds of books appeared explaining “how to feed and to keep babies clean, how to medicate sick children, how to toilet-train toddlers efficiently, and, above all, how to stimulate and educate children from an early age.” Special mention goes to the saloniste Louise D’Épinay, who argued against theories of parenting based on natural instincts and capacities. She insisted that (as Sennett writes) “in place of blind love or command, there need to be objective, rational, guiding standards” for how to nurture infants, and that “implementing such standards requires skill that any parent develops only though practice.”

Of course handbooks dispensing such advice are ubiquitous today, and to this extent most parents now subscribe to the idea of parenting as a craft. Then again, I’m aware that parenting philosophies clash on many questions of objective technique versus more freeform, “baby-led” methods, so I’ll just repeat that I’m a beginner who claims no special insight here. Besides, the knowledge that underpins parenting standards seems to be in constant flux. Much of the official advice dispensed by midwives and health visitors comes with an acknowledgement that our parents’ generation was told something completely different.

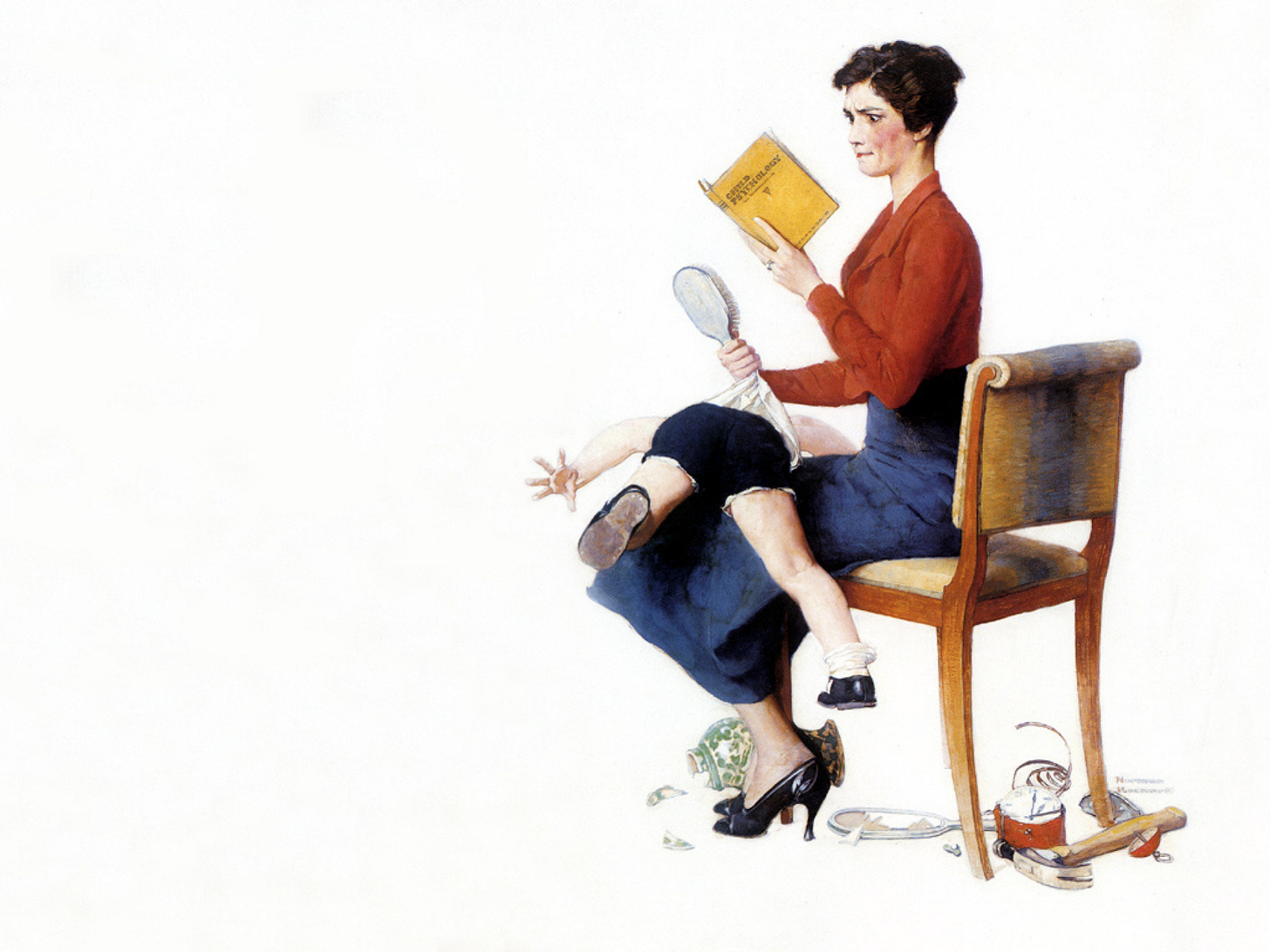

In the eighteenth century, rational parenting could be contrasted to the folk wisdom and popular intuitions that parents had always relied upon. Yet the distinction between reason and prejudice is not always very clear. There is a wonderful Norman Rockwell illustration, which appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1933, showing an exasperated mother with her son over her knee, ready to be spanked, while she peers into a volume titled Child Psychology. Perhaps the mother is seeking “expert” permission for a punishment that is really motivated by tradition and emotion; or perhaps the text has suggested the punishment to her, after dressing it up in scientific jargon. Either way, the image seems to suggest that parenting is bound to be a messy mixture of custom, sentiment, and efforts at rational understanding.

The other problem is too much knowledge – or at least, too much information. In Britain, where an infant’s first mark of citizenship is the National Health Service number it gets shortly after birth, the authorities impart to parents a mass of safety instructions. This is good in principle, but I was bemused to find that many of the rules are ultimately disregarded as unrealistic by most parents, though presumably after causing them a fair amount of anxiety. The official line on sleeping, for instance, which comes from the Lullaby Trust, is that a baby should sleep by itself, in a separate space “free from toys, blankets and pillows,” and on a firm, flat mattress. The stated reason is to reduce the risk of SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome). But the same organisation reports that 9 in 10 parents sometimes fall asleep with their babies – it would take a superhuman effort not to – while online forums and word of mouth reveal that many parents find the benefits of cot bumpers and nests too great to resist.

So how great is the danger? SIDS accounts for 200 deaths annually in the UK, or about 0.03% of the number of babies born (down from 0.05% in 2004). Around half of SIDS cases involve co-sleeping, but these may be associated with “hazardous circumstances” such as drunkenness or sleeping in a chair. For comparison, the number of families who take legal action against the NHS for obstetrics errors each year is over 1,000.

Should the authorities place less emphasis on guidelines when the risks are minuscule? I honestly don’t know. What does seem clear is that, the more data we gather about babies and infant development, the more we will find tiny statistical effects which can be classified as risks or opportunities. This information will find its way to every nervous parent typing questions into a search bar on their phone, who will then have to decide whether it justifies the burden of changing their behaviour. I am starting to realise, in other words, that the craft of parenting is not just about gathering knowledge and experience, but judging which knowledge and experience to act on.

I'm in no position to give advice, but here goes anyway.

Next summer go to the beach. The South Shore of Long Island (NY) would be good. Sit near the lifeguards where the families all sit. And watch the mothers.

Many of them develop an admirable, James Bond-like, unflappable quality. Learn to imitate that, even if you don't feel it. Learn to pretend that you're doing the crossword puzzle or reading a book. Pretty soon you'll start feeling better and the wee princeling will be happier, too (if that's possible; the beach is already Paradise enough for kids).

Best of Luck!

P.S. Don't think about sharks.

Be prepared to change, in very significant ways. The innocent will of my third child felt ruthless at first to me. I had to change. That was 16 years ago. One of the best things I did