On the Giant Sphere in Las Vegas

A microcosm of modern life?

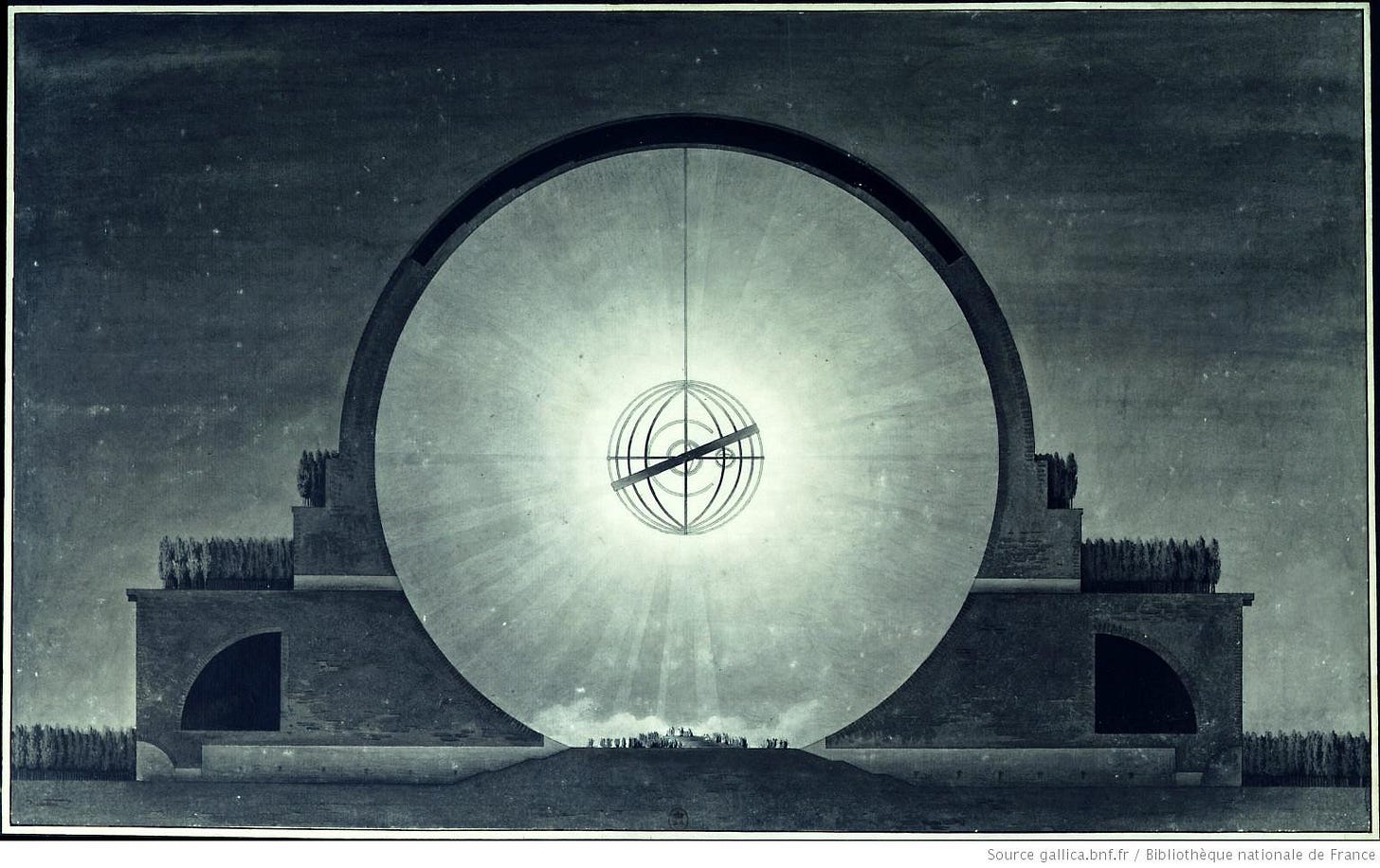

A vast sphere, 500 feet high, emerges from a base of towering ramparts. Inside this great circular space, day and night are reversed. Sunlight enters the dome through dozens of small openings, like pinpricks, simulating a starry sky. At night, a fire is suspended in the centre of the dark sphere, representing the sun.

This is one of the sublime structures imagined by the neoclassical architect Étienne-Louis Boullée in the late 1700s. He designed it as a cenotaph for the natural philosopher Isaac Newton, then regarded as a saint of the Enlightenment. Like all Boullée’s grand fantasies, there was no chance of this monument ever being realised; it exists only in the form of his exquisite ink wash drawings.

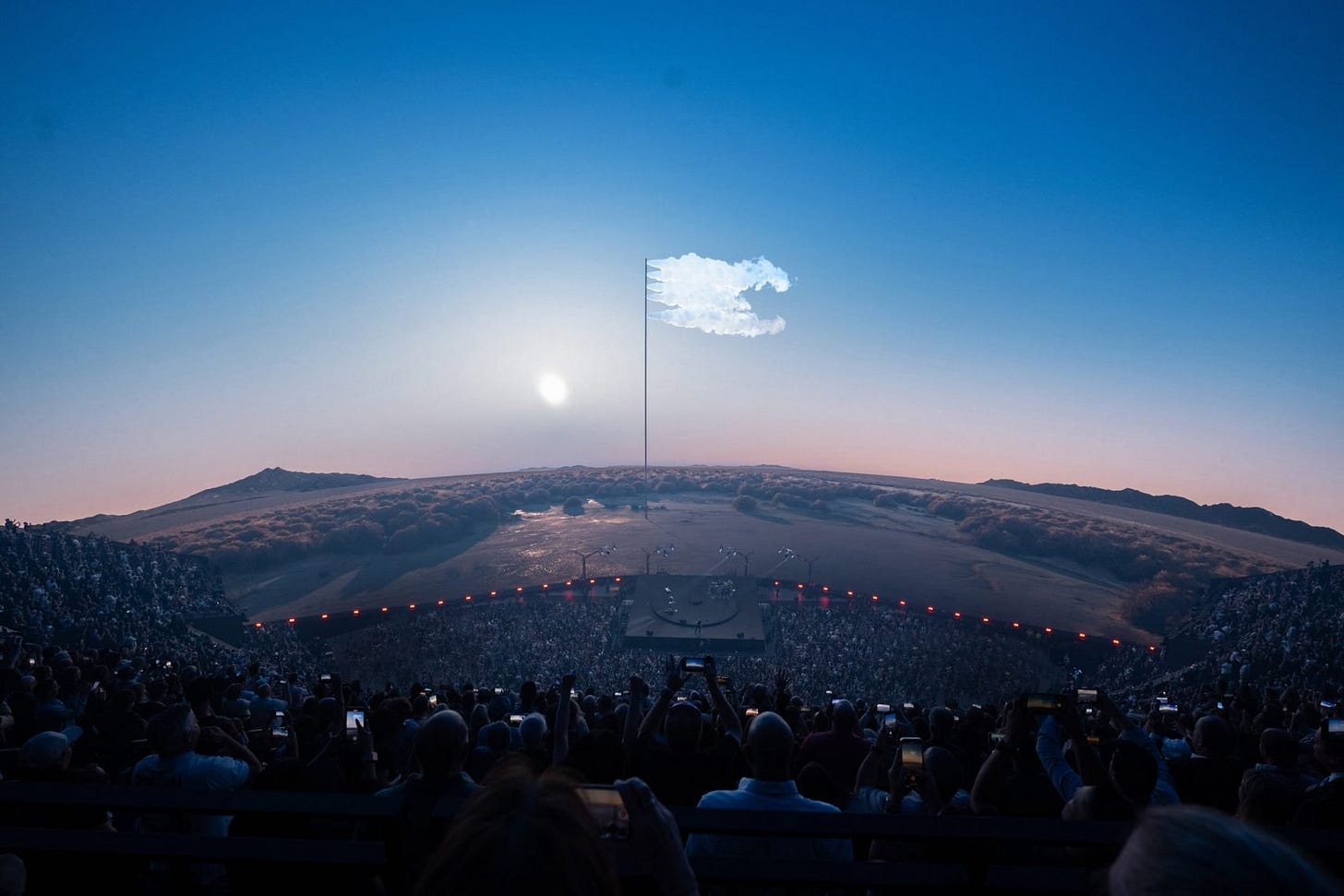

This week, another very big spherical structure caught the world’s attention. Designed by architecture studio Populous, the MSG Sphere is a new Las Vegas entertainment venue. It is coated with LED screens both inside and out – some 700,000 square feet of them – allowing it to hypnotise audiences and dominate the surrounding cityscape with spectacular displays. Since July, the Sphere has announced its presence by transforming into, among other things, the planet Earth and a gigantic blinking eye. At the grand opening last weekend – a U2 concert, predictably – the visuals inside the venue included a panoramic desert landscape and a sky crowded with hundreds of animals, reflected in a horizon of silver water.

Insofar as this building can be seen as a distant echo of Boullée’s imagined monument – and strangely, the two spheres have roughly the same diameter – it is a useful reminder that such spectacles are not entirely a modern perversion of architecture. Visionaries have long dreamed of built forms that overawe the senses and emotions, and even structures that change their appearance for scenographic effect. At some basic level, one can only marvel at the aesthetic and technical feats our era is producing, surpassing even the most hallucinatory blueprints of earlier centuries.

Ultimately though, such comparisons only heighten the impression that the giant sphere in Las Vegas is something particular to our moment in history, perhaps even a model of it in miniature.

For Boullée, the purpose of emotional affect was to direct the mind towards transcendent realms, worlds beyond the mundane and immanent. His sphere evokes the Platonic perfection of geometry, a Romantic reverence for nature’s terrifying beauty, and the virtue of an ideal state. The Sphere in Las Vegas embodies another, very different notion of transcendence, located in fleeting experiences. This is what our culture typically promotes as the source of meaning in life: experiences, special moments that offer enrichment or euphoria or emotional satisfaction. They come from visiting new places, trying new things, or indeed partaking in the delights of the hospitality and entertainment industries.

The MSG Sphere is the culture of experiences in a nutshell. Such “immersive” entertainment promises a kind of transcendence through stimulation, not to mention simulation. It reveals a higher reality that is not abstract and eternal, but transient and sensory, the audio-visual equivalent of a drug trip.

And yet, looking at videos of the concert at the Sphere, we don’t see an audience immersed in the moment; we see thousands of smartphones held aloft, creating a digital record of it. The value of experiences supposedly lies in their immediacy, yet we cannot properly enjoy them unless we destroy that immediacy by embalming them as photographs and videos. We kill the butterfly to pin it in a frame. One commentator captured this paradox nicely when he suggested that, in future, virtual reality technology will not replace venues like the Sphere, but compliment them, since the audience will be able to relive its unique experience through a headset afterwards.

Maybe we are so saturated with media that we simply see the world from the perspective of our cameras and their ability to share images; we value an experience because the audience that lives in our mind values it. The result, of course, is that the world is increasingly curated to appeal to this impulse. We want images, so settings are arranged as images for us, from restaurants to quaint, tourist-hungry towns. To raise a camera in these places is to realise that the photograph has already been prepared for you – or for your audience – like a visual souvenir. The strange disappearance of unmediated reality we see at the MSG Sphere, where not only the audience but the event itself is a wall of screens, only makes this wider development explicit.

With the combination of screen and camera, technology has fused the acts of showing and watching. The troubling implication of this, which we are becoming more acquainted with every day, is that when you are seeing something, there is a good chance you are also being seen. And so it transpires that the entertainment mogul who built the MSG Sphere, Jim Dolan, employs facial recognition technology at his venues in New York, including the sports arena Madison Square Garden. According to the New York Times, Dolan uses this tech to deny entry to fans who criticise his management, as well as lawyers who are suing him. It should come as no surprise that the master of spectacle is also a master of surveillance.