Nostalgia for the Concrete Age

A fondness for post-war architecture shows even progressives mourn the past

Our forebears did not think as we do. In the late 1940s, the Soviet émigré Berthold Lubetkin served briefly as chief architect for Peterlee, a new town in England’s northeast coalmining region. The glorious centrepiece of Lubetkin’s vision? A highway carving through the middle of the town.

“Young couples,” he dreamed, “could sit on its banks watching the traffic, the economic pulse of the nation, with coal and pig iron in huge lorries moving south, while from the south would come loads of ice-cream and French letters.” (A French letter, in case you were wondering, is a condom).

Today this sounds vaguely dystopian, like a dark fantasy from the pages of J.G. Ballard. The English motorway, now a site of daily torture for thousands, is not easily romanticised. But the strange thing is that, if Elon Musk suddenly stumbled on some new mode of transport that made our roads obsolete, Lubetkin’s poetic view of asphalt and traffic would quickly resonate again. The M6 would become the subject of coffee table books.

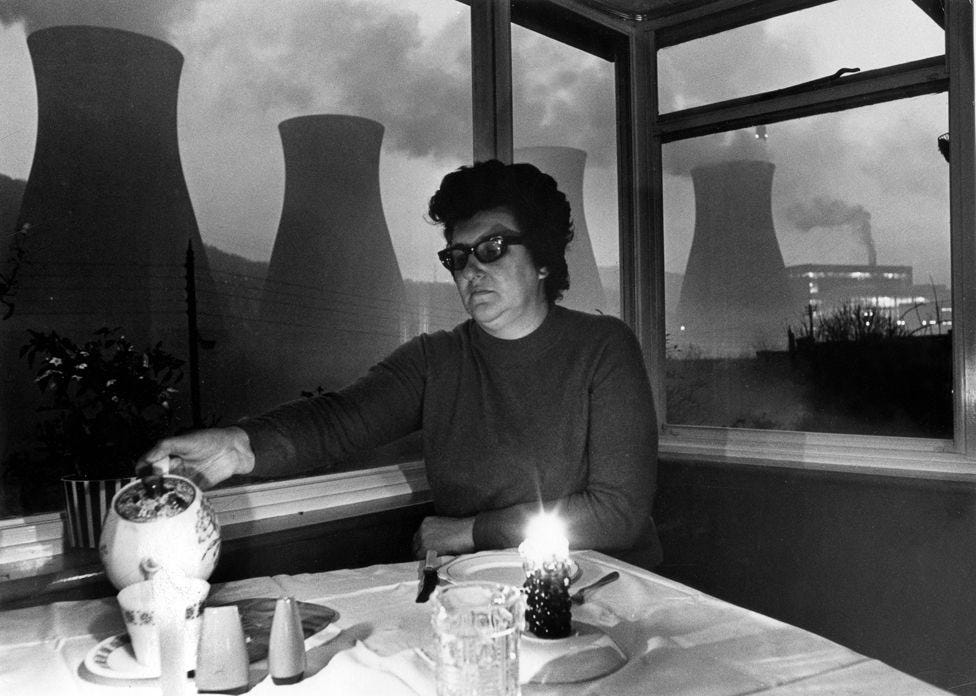

That is the pattern we see with other architectural relics from the decades following the Second World War. Concrete is cool again. This week, I visited boutique fashion brand Margaret Howell, which is marking the London Festival of Architecture with a gorgeous photography exhibition on the theme of British cooling towers. These are the enormous, gracefully curving concrete bowls that recycle water in power stations. Except they are now disappearing along with the UK’s coal-fired power stations, and so the 20th Century Society is campaigning to save some of these “sculptural giants” for the nation’s heritage.

Elsewhere at the LFA, there is an exhibition celebrating gas holders, another endangered species of our vanishing industrial habitat. And this is all part of a much wider trend over the last decade. In that time, a number of histories have been published that try to rebut the negative view of Modernist architecture from the 1960s and 70s. As I mentioned in an earlier post, there was outrage among design aficionados when, in 2017, the Brutalist estate Robin Hood Gardens was demolished.

The mania is still growing. In Wallpaper magazine’s recent list of exciting new architecture books – a good barometer of fashionable taste – there are more than ten which celebrate post-war Modernism and Brutalism.

I welcome this tenderness for a bygone age. We should save our finest cooling towers and council estates from the wrecking ball. Some of them are very beautiful, and certainly an important part of our history. But I am a romantic in these matters; I see just about any scrap of the past as the spiritual equivalent of gold or diamonds. The question is why creatives, a devoutly progressive bunch, have become so attached to the concrete age. They don’t show the same sympathy for the dominant tendency of any other period. Wallpaper does not promote eulogies for Georgian terraces or Edwardian monuments.

There is doubtless an element of épater la bourgeoisie here. Creatives like to kick against conventional taste, which has long regarded mass-produced housing as depressing and Brutalist buildings as an eyesore. Fashion goes where the unfashionable do not, which in the built environment means exposed concrete.

There are deeper reasons of course. They can be seen in Lubetkin’s utopian vision of the highway, a structure that brings workers the rewards their industry deserves. In Britain and elsewhere in western Europe, the post-war decades were a time of unusual commitment to equality, solidarity and social progress, the golden age of the welfare state. This “Spirit of ’45,” as Ken Loach’s sentimental film called it, is uniquely cherished by the British left in the same way the New Deal era is by the American one.

Crucially, the architecture of the time is not only seen as embodying these ideals, but as embracing a bold, modern approach to form at the same time. It represents the dream that artistic virtue can dovetail with social virtue. This is most obvious in some of the ambitious housing, schools and municipal buildings designed between the 1950s-70s, but even the cooling towers are part of this story. They were born from the nationalisation of Britain’s electricity grid in 1948.

What makes this lost world feel relevant now is that it ended with the arrival of the neoliberal era in the 1980s, and opposition to neoliberal principles has defined progressive politics in recent decades. Champions of the post-war project never fail to mention that, while it was far from perfect and sometimes disastrous, at least there was a commitment to providing decent conditions for everyone.

Still, let’s not pretend this reverence for the past is just about finding inspiration for the future. Empathising with the hopes and dreams of a distant era, savouring its aesthetic flavour, feeling the poignance of its passing: there is a word for this combination of emotional acts. It is nostalgia.

Of course that word is a dirty one now. At the cultural level, it is associated with irrationality, resentment, and hostility to change. It is pinned on old people who vote the wrong way. But that, surely, explains the appeal of the concrete age. Thanks to its creative and political legacy, it provides cover for people of a progressive bent to indulge the nostalgic sentiments they otherwise have to suppress.

It’s unfortunate that such alibis are needed. Nostalgia is not a pathology; it is part of the human condition. A deep-felt sense of loss is the inevitable and appropriate response to the knowledge that all things in this world, good and bad, are transient. The pathos of that fact can be deflected and disguised, but it cannot, ultimately, be denied.