Introduction to The Pathos of Things

My perspective on design and the world of artefacts

Some years ago, I heard about a team of art handlers who had spent the morning cutting up sculptures with a chainsaw. I was working as an art critic at the time, and the gossip often demanded a strong stomach. The sculptures in question had been shipped over from Africa (I never found out where exactly) by a private London gallery, since collectors had developed a taste for contemporary African art. But when the artworks failed to sell, the artist couldn’t afford to pay half the shipping fees to get them back. So they were simply hacked up and disposed of like some abandoned car.

I’d like to think my first reaction to this story was sympathy for the exploited artist, but what I remember is being fascinated by the transformation of those artworks. One moment they had been potential vehicles of beauty, social status and even spiritual value. The next moment they were driftwood. What made this sacrilege possible? Maybe they were bad sculptures, or maybe the artist wasn’t famous enough. Maybe fashion had simply moved on.

It was questions like this that eventually dragged me into the orbit of art’s vulgar cousin, design. Admittedly that orbit is quite wide. Design encompasses a vast range of practices, from fashion design to software design, from menu design to engine design. It could refer to almost anything that involves the application of practical knowledge and creativity to a particular task. What appealed to me, though, was not the ingenuity of designers as seen on the pages of Dezeen.

I was interested in the roles played by artefacts, by the products of design, in the drama of our lives. I was interested in how and why we value certain objects (or indeed fail to value them), and in the unusual perspectives that emerged from looking at the ways artefacts are made, presented and used. Over time I found these subjects compelling enough that I thought they deserved a newsletter, The Pathos of Things, whose first instalment you are reading now.

In some ways the journey from art to design was not a long one. Certain design fields, like architecture, have long been overtly artistic. I recall seeing for the first time an image of Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower observatory, a kind of streamlined stucco spaceship stranded in the Potsdam landscape, and instantly recognising the aura of a great artwork. Regardless of whether I liked this building, it seemed to be saying something important.

Mendelsohn’s tower was a landmark of expressionist architecture, and a quixotic attempt to represent the revolutionary implications of Albert Einstein’s breakthroughs in physics. But a building does not need to be a masterpiece to tell us something about the society in which it stands. Public designs, including not just architecture but transport systems and even cities, offer insights into lives of the people using them, as well as the political ambitions of those who commission them.

Today formal beauty and technical accomplishment are features of design far beyond architecture. Consumerism and the ever-growing presence of visual media have brought about a great aesthetic awakening in modern cultures, so that you need no longer be a connoisseur to appreciate stylish light fittings or headphones. By the same token, more areas of design are becoming bound up with considerations of status and taste. It increasingly feels like our identity is at stake in our choice of furniture and kitchen appliances, sportswear and website designs. People who might shrug at the destruction of an artwork would feel a visceral sense of loss if you took a chainsaw to their favourite design item.

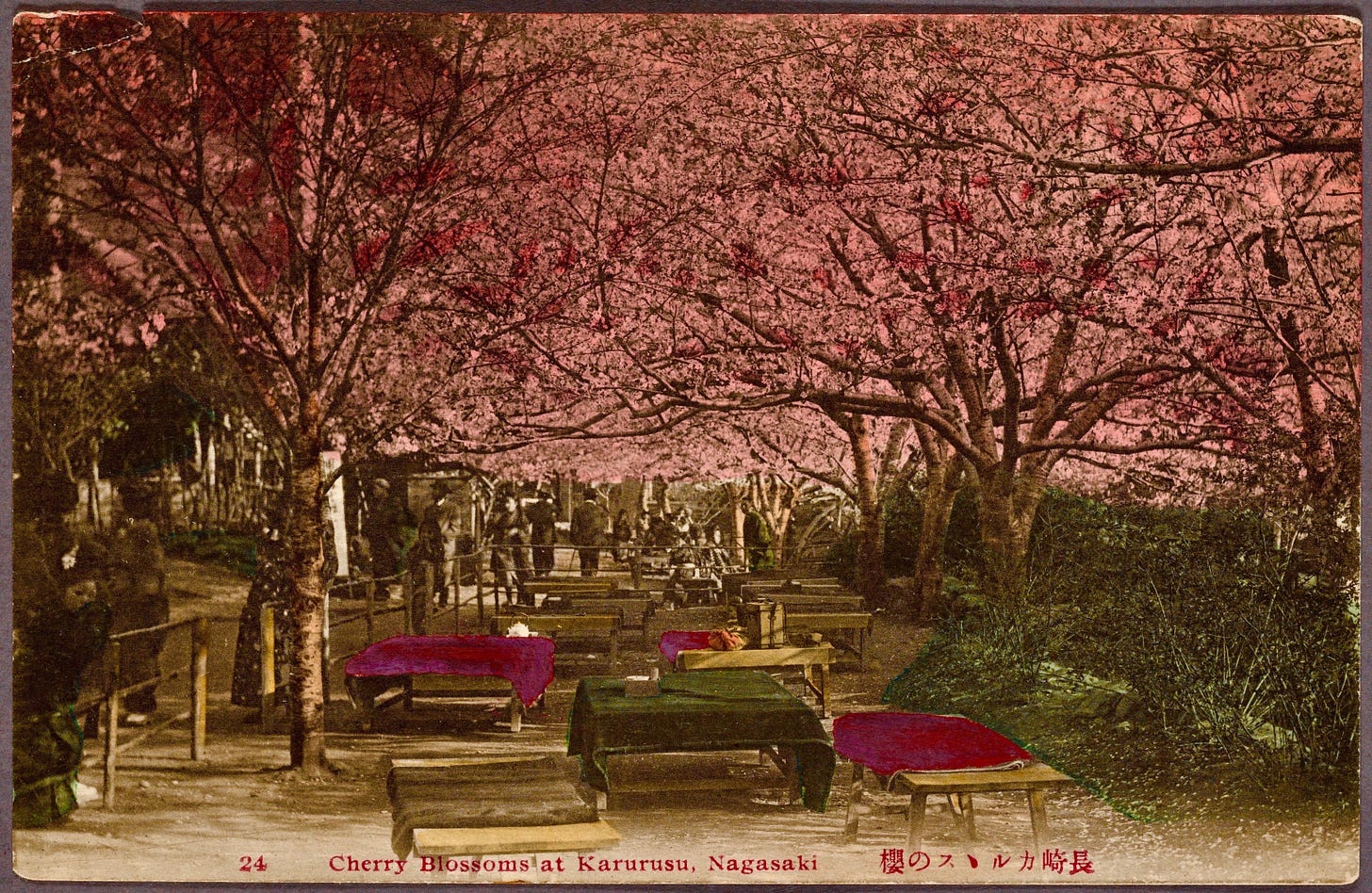

The ephemeral nature of such consumer design, driven by novelty and the churn of fashion, can still make it seem like a trivial subject. I am alluding to this, in a slightly playful way, with this newsletter’s name: “the pathos of things” is a Japanese idea referring to the beauty of the impermanent, as symbolised by the brief flowering of cherry blossoms. The transience of consumer culture might not be beautiful, but it is profound in its way, since it is part of the experience of constant flux which frames the human condition in modern societies. Besides, changes in style and trend often map onto deeper transformations, revealing new forms of social identity or the impact of new technologies.

Ultimately, design can be seen as an on-going dialogue between those who make things and those who use them, a dialogue full of cunning and obfuscation. Where it faces an audience, design is trying to shape perceptions: trying to appear useful, attractive or inspiring. It may have its own vision to communicate, but it is careful to know its interlocutor, sometimes falling in with trends that it did not start, sometimes bending attention and desire towards its own ends.

This points to another meaning of “pathos”: a technique of persuasion, involving an appeal to the emotions. Recognising something as a product of design means being conscious of its efforts to engage us, and conscious at the same time that artefacts can take on a significance beyond what the designer intended. But it also means trying to see past the pathos of things, past the web of feelings and impressions in which contemporary culture immerses us, to understand what is happening behind the scenes.

Many forms of design are not visible: the design of tools, machines, systems and processes. These functional elements provide the framework for design to flourish in its aesthetic capacity; without them, engaging artefacts cannot be created or presented to their audience. Commodities are designed, but so are the factories that make them, the containers that transport them, and the shop-fronts or software programs that advertise them. A glorious urban plan needs drainage systems, just as a digital interface needs algorithms.

It is often in this background world of instrumental design that the most illuminating discoveries can be made. This is where we find the technologies that have shaped our lives without us even realising it, and where we encounter the logic of efficiency that determines a great deal about our designed environment.

In other words, examining the role of design in our lives can lead us in numerous directions. Artefacts find their immediate significance in the ways we use and value them, but they also allow us to situate ourselves within a complex, ever-changing world. We can, for instance, use the products of fast fashion to glimpse the dynamics of online culture, and the design of microchips to understand the nature of contemporary capitalism. We can use the interiors of restaurants and hotels to chart the emergence of new worldviews, and high-speed trains to track the rise of a new China. We can consider how the products of design reflect our perceptions about time, power, and what it means to be modern.

These are just a few of the subjects I will be writing about in the coming weeks and months, at The Pathos of Things.