How Images Remember

The art historian Aby Warburg revealed the hidden depths of mass culture

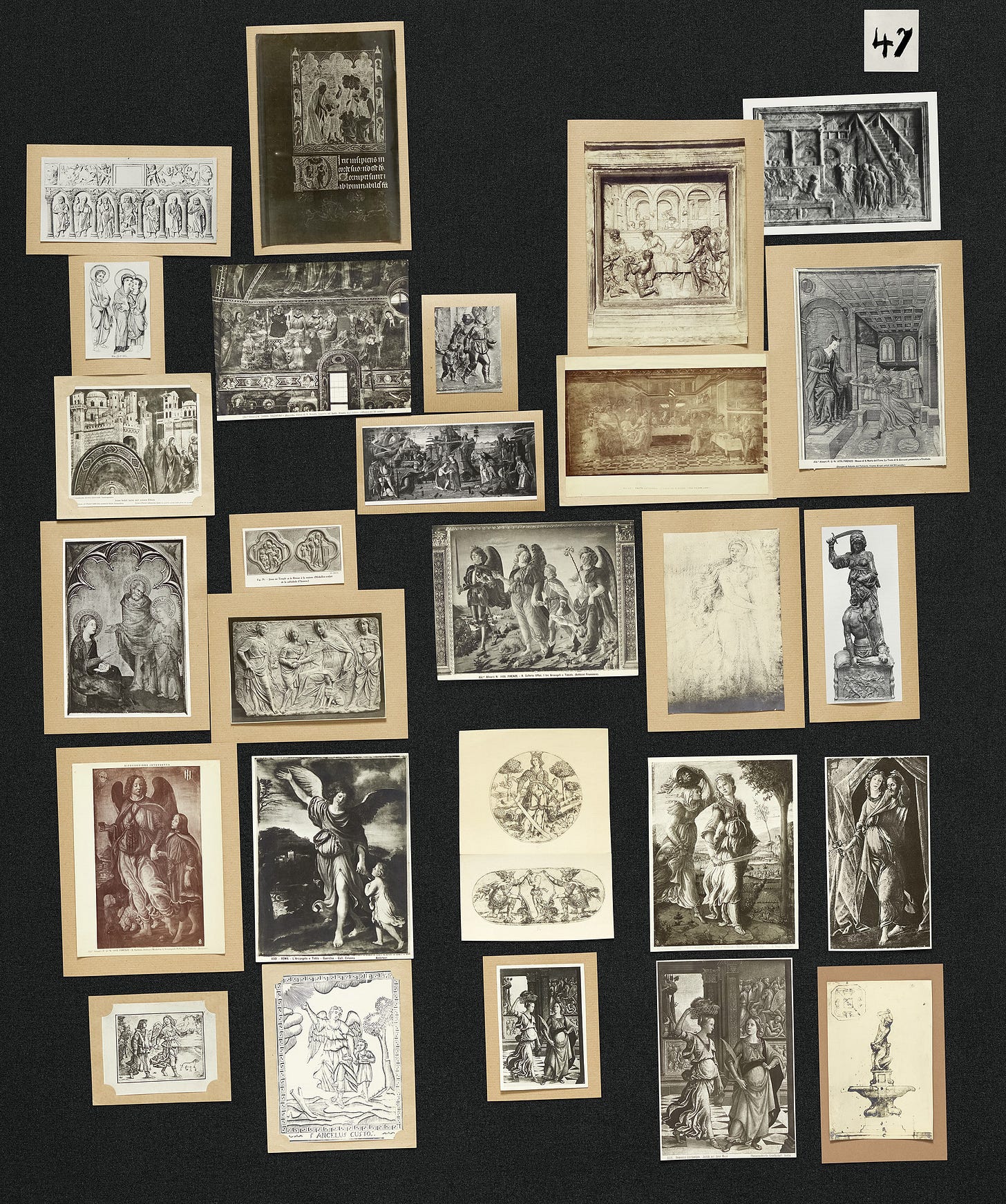

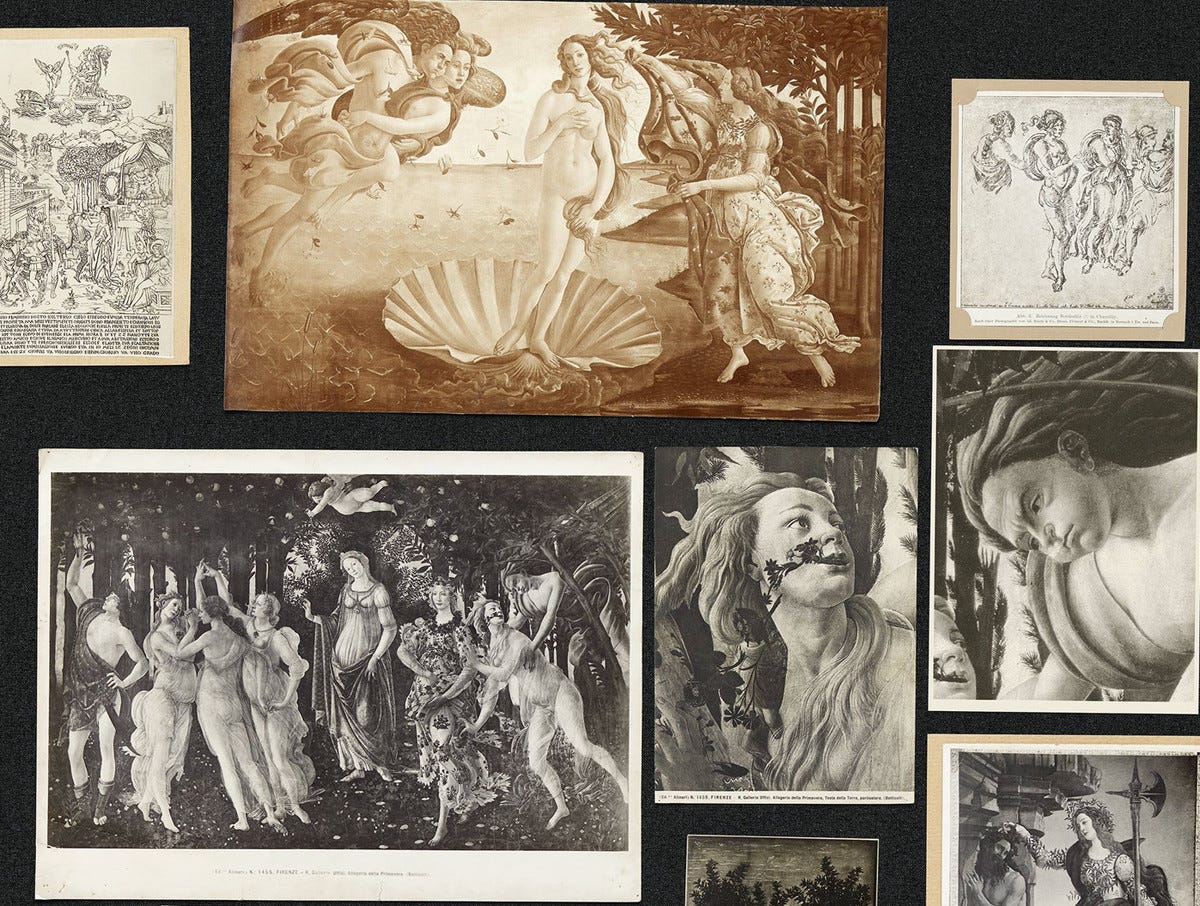

In the late 1920s, during the final years of his life, the art historian Aby Warburg embarked on one of the most remarkable intellectual projects of the 20th century. Titled in German Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (The Image Atlas of Memory, or Memory Atlas), it was a vast compendium of images, documenting the persistence of certain symbols, gestures and themes across centuries of visual culture.

Photographs of artworks and artefacts swarm across dark hessian panels, accompanied by press cuttings and other mass media. Between these images is a space charged with echoes and affinities. What is the significance of a body in motion, as expressed by the garments that swirl behind it? What ancient energies resurface in a picture of a woman swinging a golf club? What cultural evolution is described by the characters that different eras have projected onto the stars? These are the kinds of questions raised by the Memory Atlas and its mysterious dialogue of images.

Warburg was a fascinating man and a deeply idiosyncratic thinker. He was also a visionary, in that he saw images not as individual works, but collectively, as a medium in which the emotions and ideals of a culture reside – an insight we almost take for granted today. If you’d like to know more, I’ve written a longer piece about Warburg for Engelsberg Ideas, which was published this week. What I want to do here is say something about how Warburg has helped me appreciate the objects and images which constitute our own world.

Images, for Warburg, are bearers of memory; they remember not just the things they represent, but the other images which taught them how to represent. Images communicate with expressive formulas, and these formulas are adapted from earlier images, which in turn have adapted them from still earlier ones. This means, as I wrote in the Engelsberg piece,

when we need to express or represent an idea, we draw from a stock of gestures and symbols whose meanings are kept alive in our culture by the presence of earlier representations. In this way, images can travel across centuries, being recalled repeatedly into new contexts and acquiring new layers of meaning.

In many cases, it is only by reference to this “memory” that we can fully understand why a symbol means what it seems to mean. To illustrate this, I used the example of “taking the knee,” a gesture now associated with protests against racial injustice, but which draws from a long history of Christian body language for its impact.

On a more basic level though, this idea of memory simply calls our attention to the fact that every human artefact belongs to a history which has determined its character. This is an obvious point, but one that can add a great deal of depth to the world. From its consumer products to its vast oceans of digital imagery, the aesthetics of mass culture often appear transient and superficial: a blur of ephemera driven by fashion, money and sheer volume. Yet even the most banal object, even the most fleeting image, stands in some line of descent from earlier iterations of the same form or idea. Tracing these threads will invariably disclose something about how the world itself has changed.

Few images are as ubiquitous today as corporate logos – looking around my desk, I suddenly see them stamped everywhere – yet this form of symbolism is steeped in time, with origins in medieval heraldry. Much is revealed by the journey from the family crest to the visual signatures of global firms, not just a radical transformation in the nature of power, but a surprising continuity in how power is represented.

The first Starbucks logo, designed in 1971, was adapted from a 16th century Norse woodcut portraying a double-tailed siren. That mythological creature has its own, much longer history, going back as far as a mosaic in a 7th century Italian church. There is a pleasing mischief in this piece of branding – a siren, like a coffee shop, lures passers-by into a fatal entrapment – but more telling is the logo’s subsequent evolution. Over the decades it has been drastically simplified, all but erasing its original identity, as Starbucks has evolved from a local business in Seattle into a byword for globalisation.

The logo of the automaker Volkswagen tells a darker story. During the 1930s, the circle surrounding the VW symbol was a cogwheel sporting thick mechanical teeth. This detail alluded to the company’s parent organisation, the German Labour Front, founded by the Nazi Party after it suppressed the country’s trade unions (the Labour Front’s own badge showed a cogwheel enclosing a swastika). The cogs have long since been purged from the VW logo, but the circle remains, a reminder of the German car industry’s origins in an age when authoritarian regimes tried to lead the world in mass production.

As it happens, I have in front of me another image of a cogwheel, with a very different meaning. It is the “action” icon in my MacBook’s Finder application. It seems strange, at first glance, that this physical symbol has found its way into the repertoire of the digital age, but looking at the widgets on my smartphone I see countless similar examples: an envelope, a handheld camera, a clock face, a pen, a pad of paper, and so on. It’s plausible that some of these items will eventually disappear from everyday use, leaving only their symbols behind, at which point someone will need to investigate the origins of those images as well. These are dematerialising objects, in transition to pure iconography.

Aby Warburg spent most of his career tracing visual forms that evolved over centuries, in paintings, sculptures and engravings. Looking at his Memory Atlas, you can almost feel the moment of insight when he realised the detritus of mass culture was no less a vehicle for memory. In fact, the speed at which the modern world changes, constantly erasing the evidence of its past, only makes this temporal dimension more important. It can feel like we are trapped in an eternal present, whereas we are really surrounded by half-buried stories.