Guns, Geeks, and the Spectacle of War

The Internet has renewed an age-old fascination with military gear

“This is the most up to date map I have seen in the past 3 hours. Thank you.” Let this tweet give you some sense of the devotion, or obsession, with which people are tracking the Ukraine war on social media.

As technology provides windows through the fog of war, an army of observers studies the implications of every new video, image and map relating to the battlefield. The most committed among these war-watchers, however, take a special interest in the sequences of numbers and letters that identify weapons.

T-72, BM-27, BMP, ATGM, Ka-52, AGM-114C, T-80BV, S-300: most of us only encounter this kind of nomenclature when we need to organise a fridge repair, but for the initiated, these codes give meaning to the constant stream of media coming from the frontlines.

“More photos of that ancient but powerful M-240 240mm mortar in use with Ukrainian forces. As can be seen it is used with 53-F-864 HE FRAG mortar bombs - each weights 130kg, packs 32kg of explosives and can be fired as far as ~9.65km.” That’s a typical post from one of the most prominent accounts documenting the war, Ukraine Weapons Tracker (a post that received 280 shares, 2,700 likes and almost forty replies). Though in certain cases, and especially when studying the smoking ruins of a destroyed tank, jet or artillery piece, identifying the item involves an eager debate.

This subculture fascinates me because it recalls an age-old story of design obsession, namely, the geeky fixation of boys with military hardware. (And I do mean boys: some leading figures in this realm are barely twenty years old, having started out as teenagers). But while it has all the features of an obscure Internet niche, it isn’t actually that obscure any more.

In a world increasingly destabilised by conflict, amateur battlefield sleuths have become a valuable information source. Their cataloguing of equipment, losses and troop movements is monitored by professional analysts and journalists, not to mention organisations documenting war crimes. At the same time, they provide a channel for a new form of propaganda, as the combatants seek to spread evidence of their battlefield achievements. And so a growing public audience, drawn by some ambiguous combination of information hunger and morbid curiosity, finds its social media feeds dotted with daily scenes of war.

At the centre of all this is the emerging field of OSINT, or open-source intelligence: a network of largely amateur researchers who use public information sources like Google Maps, Maxar satellite imagery and security camera feeds to establish what is happening in war zones. OSINT began taking shape after 2011 with the Syrian civil war, and gathered momentum after 2014, with the Russian invasion of Crimea and the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

One prominent OSINTer, Justin Peden (Twitter handle Intel Crab), was thirteen when he apparently “created a Twitter account pretending to live in Donbas in order to network with Ukrainians… who he spoke to using Google Translate.” That was in 2014. Calibre Obscura, one of the researchers behind the Ukraine Weapons Tracker account, is reportedly a twenty-something IT worker in the UK, who says his knowledge of military equipment is “ninety percent self-taught.”

The journalistic value of this research is beyond doubt, especially when it comes to conflicts in places like Syria or Yemen, where information is limited by a shortage of Internet access and foreign interest. Nonetheless, the legions of OSINT fans who follow and engage with this material online are evidently extending the tradition of military hobbyism.

Online weapons spotting is the descendant of model airplanes, figurines (lovingly painted and arrayed in formation), war games with detailed rulebooks, the military history volumes beloved of men over forty, war films, video games, and the Hardcore History podcast. This species of enthusiasm resembles that lavished on toy train sets, power tools and cars. But military hobbyism seems unique in the way it combines the satisfaction of well-made tools, the appeal of martial discipline, the drama of history and the subconscious fascination of violence.

This imaginative appeal can arguably be traced back to Homer’s Illiad, with its reverence for bronze spears and chariots. A more recent source is the mythology of the American west, where the functional beauty of the Colt revolver symbolised the power of design in a world of rugged chaos. The same attention to detail is shown by video-game developers today, as they carefully simulate the look and feel of the firearms players select from their menus.

The fascination with modern military design stems partly from its distinctive character, for these are mass-produced artefacts outside the realm of consumerism (American gun culture notwithstanding). The huge government budgets assigned to military equipment make this a rare instance where factory methods are combined with high levels of quality and sophistication, as civilians occasionally discover when they chance upon an item of military-grade clothing.

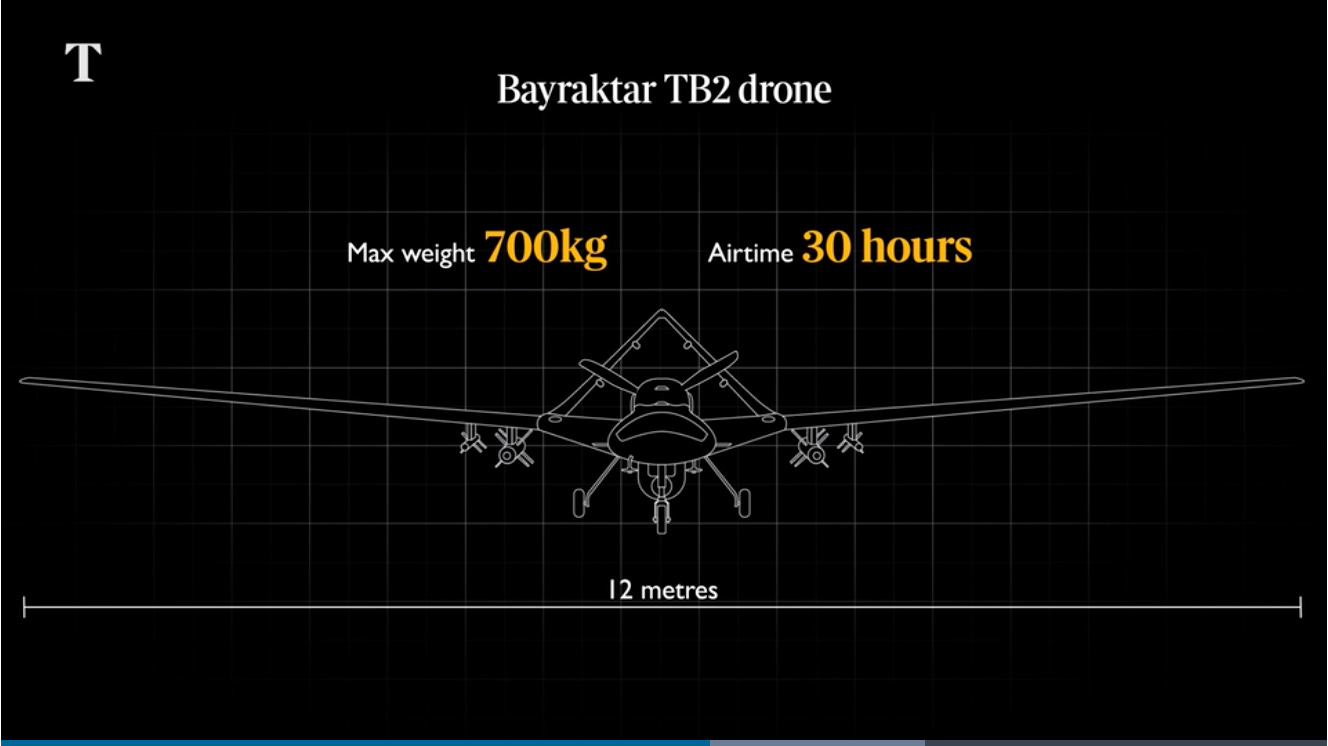

But the gun-gazing around the Ukraine war is particularly engrossing on account of another design factor: the information architecture of the Internet. With new specimens being trawled constantly from the oceans of satellite imagery and social media posts, live weapons-tracking has become a way of witnessing an epic drama unfold in real time, and in the congenial setting of a chatroom. The appeal of this format is suggested by the way popular interest in the war has been channelled through a series of iconic weapons: Javelin missile systems, Bayraktar drones, HIMARS rocket launchers. It’s not unusual now to find detailed infographics and videos about military equipment in mainstream publications.

The unsettling thing, of course, is that unlike model airplanes and video games, the war in Ukraine is real, and this is obviously what makes it so compelling. I don’t think the real military geeks are especially voyeuristic; people who engage seriously with a subject like war tend to become conscious of that danger. It is the rest of us I’m worried about. The structure of social media, even more than TV news reporting, tends to reduce the grimmest of realities to entertainment, mixing the carnage of battlefields and bombed cities into a stream of gossip and banter.

This transformation of war into spectacle is being actively encouraged by the combatants themselves, with both armies in Ukraine choreographing and editing battlefield imagery for publicity purposes. Given that the Ukrainians are relying on public support in the west to ensure our governments keep supplying them with weapons, their ability to flood the Internet with evidence of battlefield prowess may turn out to be a crucial strategic skill.

The cost of that success, though, is a further weakening of our grip on reality. It’s increasingly unclear whether we tune in to watch disasters unfold because we are concerned with the fate of our world, or because history has become a spectator sport that is all the more exciting for having such high stakes. In fact, it’s unclear if these two things can even be separated now.