Does Social Media Design Democratic People?

The logic of mass media still permeates the public sphere

It’s difficult now to remember a time before people were freaking out about social media. It feels like the definitive form of freaking out in my adult lifetime.

The anxiety has gathered around two main points. One is the way social media reshapes our minds: the shredded attention spans, the gnawing sense of inadequacy, the addiction that makes you wander around in public staring blankly at your phone, at least until you bump into another, similarly zombified pedestrian. The other neuralgic issue is the threat to democracy. In just the last few weeks, there has been outrage at the alleged collusion of social media platforms with government agencies to impose censorship, the role of conspiracy theories in the approaching American elections, and tech billionaire Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter.

What does a design perspective reveal about these twin areas of concern, the personal and the social? It encourages us, I think, to see the large overlap between them. Design is partly responsible for the ways that technology shapes our thoughts and actions, deliberately or otherwise. And in so shaping us, it influences what kind of society we are capable of forming.

An obvious model for thinking about the Internet is architecture. The spatial metaphors we use to describe the online world – platform, site, navigation, or indeed “information architecture” – are not incidental. They reflect the fact that on the Internet, much as with buildings and physical spaces, our range of movement, our interaction with stimuli, and the general texture of our experiences are governed by structural principles and features. The purpose of social media, as a designed space, is to regulate the way we consume and produce information.

But this analogy misses a crucial fact. The interfaces we browse on social media are not the only artefact being designed here. These are really tools that design us, the human beings that use them. Their function, as dictated by the commercial value of attention, is to create people whose instinctive desire is to be immersed in a constant stream of image, text and sound. Taken together, the purpose of consumer-facing digital design is to create a world where every human activity, from work and education to exercise and sleep, is mediated by screens, apps, and other networked devices.

It is not enough to say that Spotify has reoriented the music industry towards background music that can play all day, that Twitter has turned politics into a conveyor belt of compulsive information consumption, or that dating apps have turned sex and love into an endless merry-go-round of desire, as though these are purely external events from which we could step back unscathed. These phenomena have embedded themselves in our lives because, through some combination of direct manipulation and engineered social necessity, we have been made to want them, even to feel we need them. They have been hammered into our brain chemistry by design.

Returning to our starting point, the question then arises: does social media design democratic human beings?

This takes us into the realm of subjectivity: the character of an individual’s inner life, the pattern of his or her thoughts and desires. Defining a democratic subject is probably an impossible task, but we can learn something by considering what was perhaps the prototype: the European bourgeoisie of the 17th and 18th century. In his early work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, the philosopher Jürgen Habermas showed the importance of subjectivity in one of the momentous inventions of this era: the public sphere. This was a new layer of society where private individuals came together to debate matters of governance and common concern, consciously opposing themselves to official power by forming an independent, critical body of citizens with its own ideas.

Analysing the media habits of these early modern men and women, Habermas emphasises the role of letters and psychological novels in creating what he calls an “audience-oriented subjectivity,” meaning a desire to direct one’s internal life outwards to an audience. The identity of the citizen emerged from this sense of a wider forum into which the individual’s contents should be channelled, a development captured in the peculiar emotional intensity of the portraits of the Dutch Golden Age. What began with the letter and the novel grew into another set of social technologies, constituting the public sphere: coffee houses, clubs, corresponding societies, and eventually a modern press.

The point of this stylised picture is not to provide a model for us, but to identify a basic element – an active, independent public sphere – which seems important for a democratic society, and which can only exist if individuals are subjectively inclined to sustain it.

That said, I am intrigued by the way social media echoes the “audience-oriented subjectivity” Habermas describes. The Tumblr, Instagram and TikTok generations seem to also regard their inner life as something to be projected outwards to an audience. And these platforms have certainly created a public sphere of sorts, allowing new ideologies and forms of political consciousness to bubble up from the interactions of private individuals. The movements emerging in this way have often adopted a public role in opposition to power, hence two typical kinds of political activity in the last decade have been protest and campaigns to influence private corporations.

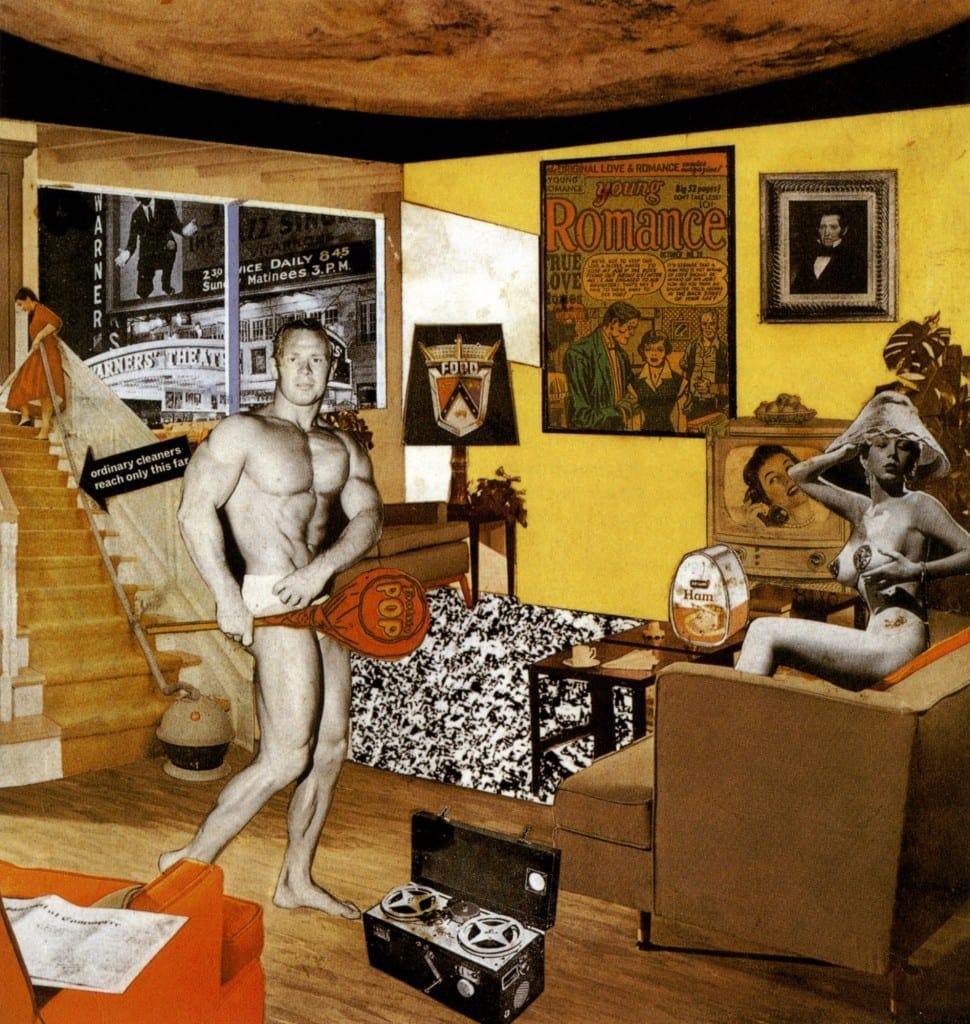

So has social media recreated something like the original democratic subject? I think not, because social media really has more in common with the era of mass media that preceded it. This sounds counter-intuitive, since we know the mainstream audiences that TV, radio and print media relied on have now splintered into a million niches and subcultures. But in terms of subjectivity, as Habermas argues, the crucial development of mass media was to turn the citizen into a consumer, by transforming the public sphere into “a sphere of culture consumption.”

During the 20th century, institutions that held power became enormous bureaucratic machines, whether it be the state, the corporation, the trade union or the political party. These institutions used mass media to create a new kind of public sphere, where they saturated citizens with their messaging. The roles were reversed: rather than the public sphere being a space where private individuals gathered in opposition to power, it became a channel through which power beamed its advertising into private life (quite literally in the case of radio and television). The public world became one of commercial entertainment, and the passive consumption of information. Companies addressed their customers as though they were serving the public interest, while politicians treated the electorate like consumers. For most citizens, public agency was reduced to the act of choosing between options offered at elections or by competing brands.

Today social media offers participation, but in so doing it has realised the logic of mass media to a whole new degree. Platforms are designed like video games, making us produce content in pursuit of recognition and status (or just to see our tally of friends, followers, matches or subscribers tick upwards); as such, they essentially enlist us as producers of mass media, seeking the largest audience available. There are plenty of popular and decent social media accounts, but the platforms still reward those who know how to push emotional buttons like a skilful screenwriter or advertiser, stimulating desire, envy, anger and prejudice. They likewise reward those who are most successful at managing their image, thereby turning themselves into a brand (which can, of course, be monetised).

And much as with entertainment in the mass media age, the point of this for the platforms is to generate advertising revenue, by fixing eyeballs and harvesting data. Giving us a voice is just a more effective away to have us consuming media all the time.

In other words, social media has re-energised the public sphere by turning it even more into a sphere of culture consumption. The process of developing ideas tends to be dominated by influencers who, as the name suggests, treat us as an audience of consumers rather than an audience of citizens. Meanwhile, the basic mechanism that makes an active public sphere possible – our desire as private individuals to address matters of common concern – is contaminated by the incentive to view ourselves as content producers, in jealous competition with others.

A popular complaint about contemporary politics is that people seem more interested in self-expression than debate, the implication being that the public sphere is being eroded by narcissism. I would say that a desire for self-expression is crucial for the public sphere; the problem is that the platforms are designed in such a way that public acceptance of that expression takes on an existential importance.

Then again, these neurotic tendencies are woven together with other, quite different currents. As I argued last year, the emergence of a new breed of charismatic leaders, from Greta Thunberg to Donald Trump, suggests that social media also provides ways of dissolving individual identity. Viral media networks have reawakened an ancient desire to find group identification through the recognition of a symbolic figurehead. This is the politics of the prophetic religious movement.

So on the one hand, the citizen becomes a content producer who needs affirmation from an audience, and on the other, we see the return of charismatic community. Between these two trends I think we can account, at least in part, for many of the developments that people find most threatening to institutional democracy, including the polarisation of debate between two strongly identified, often extreme camps. I mention this outcome in particular because it means that, like in the era of mass media, our participation in the public sphere gets reduced to a choice, with little ability to shape the alternatives on offer.

Many of these observations can be answered with a kind of cynical refrain that says, look, people are people: their affairs will always be fraught with irrationality, a desire for entertainment, the pursuit of personal gain and so on. Fair enough; it was ever thus. But democracy probably does require some degree of idealism or cultural conditioning that makes people want to be part of a public sphere, not because it’s fun or compelling or addictive, but more or less for its own sake. The social media experience makes that prospect seem quite boring, which is why this machine does not design democratic subjects.