Design for the End Times

Elaborate survival schemes for the wealthy show society is already fraying

Youtube is one of the most powerful educational tools ever created; so powerful, in fact, it can teach someone as inept as myself to fix things. I am slightly obsessed with DIY tutorials. Your local Internet handyman talks you through the necessary gear, then patiently demonstrates how to wire appliances, replace car batteries or plaster walls. I’ve even fantasised that, one day, these strangers with power tools will help me build a house.

To feel self-sufficient is deeply satisfying, though I have to admit there are more hysterical motives here too. I’ve always been haunted by the complacency of life in a reasonably well-functioning modern society, where we rely for our most basic needs on dazzlingly complex supply chains and financial arrangements. If everything went tits-up and we had to eke out an existence amidst the rubble of modernity, I would be almost useless; the years I have spent reading books about arcane subjects would be worth even less than they are today. Once the Internet goes down, I will not even have Youtube to teach me how to make a crossbow.

But what if, instead of becoming more competent, you could simply create a technologically advanced bubble to shelter from the chaos of a collapsing society? Welcome to the world of post-apocalyptic hideouts for the super-rich, one of the most whacky and morbidly fascinating design fields to flourish in the last decade.

In a recent book, Survival of the Richest, media theorist Douglas Rushkoff describes the growing demand for these exclusive refuges. Rushkoff was invited to an exclusive conference where a group of billionaires, from “the upper echelon of the tech investing and hedge fund world,” interrogated him about survival strategies:

New Zealand or Alaska? Which region will be less impacted by the coming climate crisis? … Which was the greater threat: climate change or biological warfare? How long should one plan to be able to survive with no outside help? Should a shelter have its own air supply? What is the likelihood of groundwater contamination?

Apparently these elite preppers were especially vexed by the problem of ensuring the loyalty of their armed security personnel, who would be necessary “to protect their compounds from raiders as well as angry mobs.” One of their solutions was “making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival.”

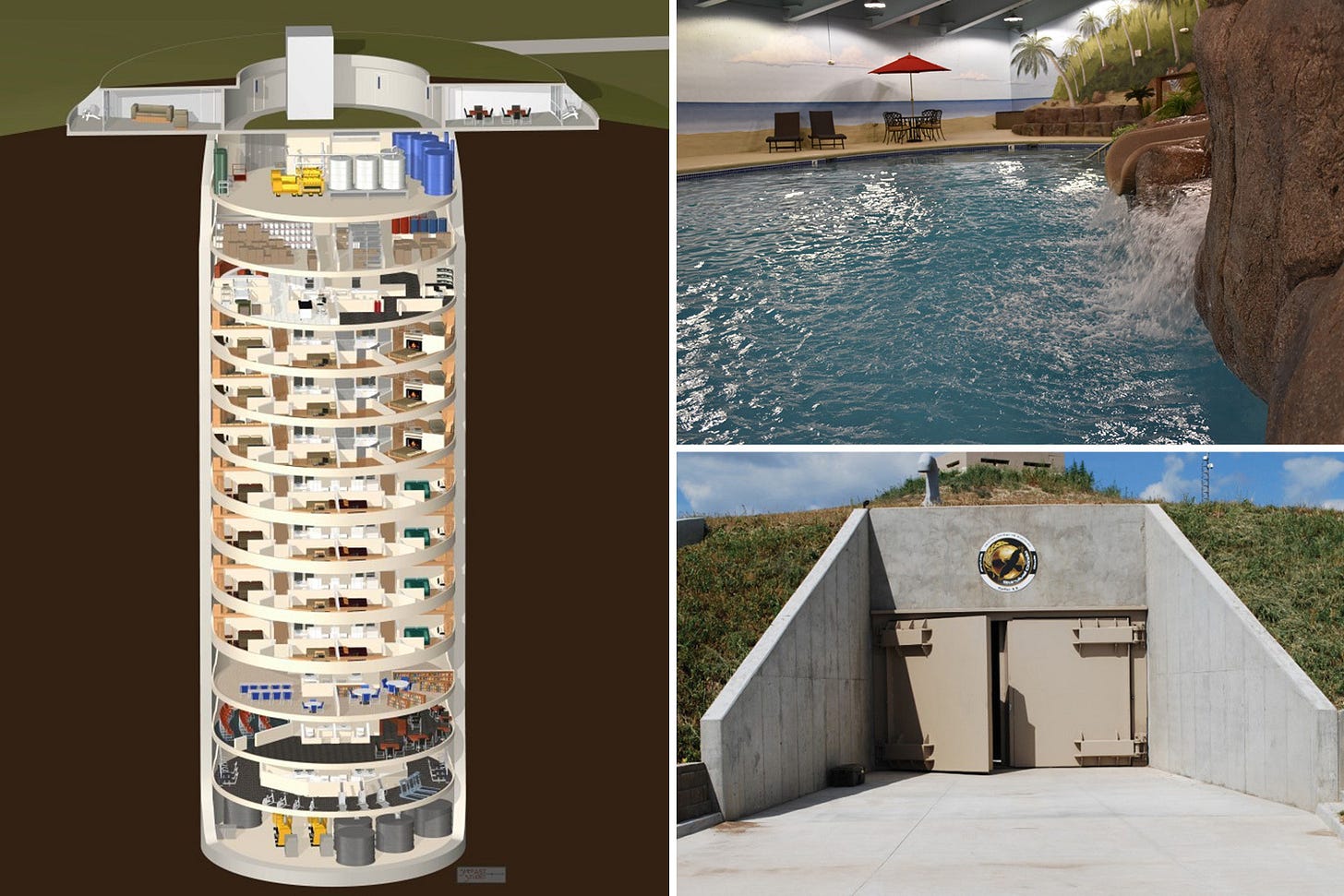

There is now a burgeoning industry of luxury bunker specialists, such as the former defence contractor Larry Hall, to address such dilemmas. In Kansas, Hall has managed to convert a 1960s silo for launching nuclear missiles into a “Survival Condo,” where seventy-five clients can allegedly outlive three to five years of nuclear winter. As I learned from this tour (thanks again, Youtube), Hall’s bunker is essentially a 200-foot cylinder sunk into the ground, lined with concrete and divided into fifteen floors. There are seven floors of luxury living quarters, practical areas such as food stores and medical facilities, and leisure amenities including a bar, a library, and a cinema with 3,000 films. Energy comes from multiple renewable sources.

What to make of this undertaking? There is a surreal quality to the designers’ efforts to simulate a familiar environment, which presumably have less to do with the realities of post-apocalyptic life than marketing to potential buyers. The swimming pool area is adorned with artificial boulders and umbrellas (yes, underground umbrellas), there are classrooms where children can continue their school syllabus (because who knows when those credentials will come in handy), and each client is provided with pre-downloaded Internet content based on keywords of their choice. You can even push a shopping trolley around a pitiful approximation of a supermarket. Honestly, it’s like the world never ended, except that a lack of space for toilet paper means you have to use bidet toilets.

But there is another way to look at these pretences of normality. Dystopian projections tend to reflect the social conditions from which they emerge: just as my own dreams of self-sufficiency are no doubt the standard insecurities of an alienated knowledge worker, luxury bunkers are merely an extension of the gated communities and exclusive lifestyles that many of the super-wealthy already inhabit. As Rushkoff suggests, these escape strategies smack of an outlook which has been “rejecting the collective polity all along, and embracing the hubristic notion that with enough money and technology, the world can be redesigned to one’s personal specifications.” From this perspective, society already resembles a savage horde lurking beyond the gate. Perhaps the ambition of retreating into an underground pleasure palace defended by armed guards is less a dystopia than a utopia.

One of Britain’s own nuclear refuges from the Cold War era – a vast underground complex in Wiltshire, including sixty miles of roads and a BBC recording studio – will apparently be difficult to convert into a luxury bunker because it has been listed as a historic structure. On the other hand, I suppose the post-apocalyptic property developers could charge extra for a heritage asset.

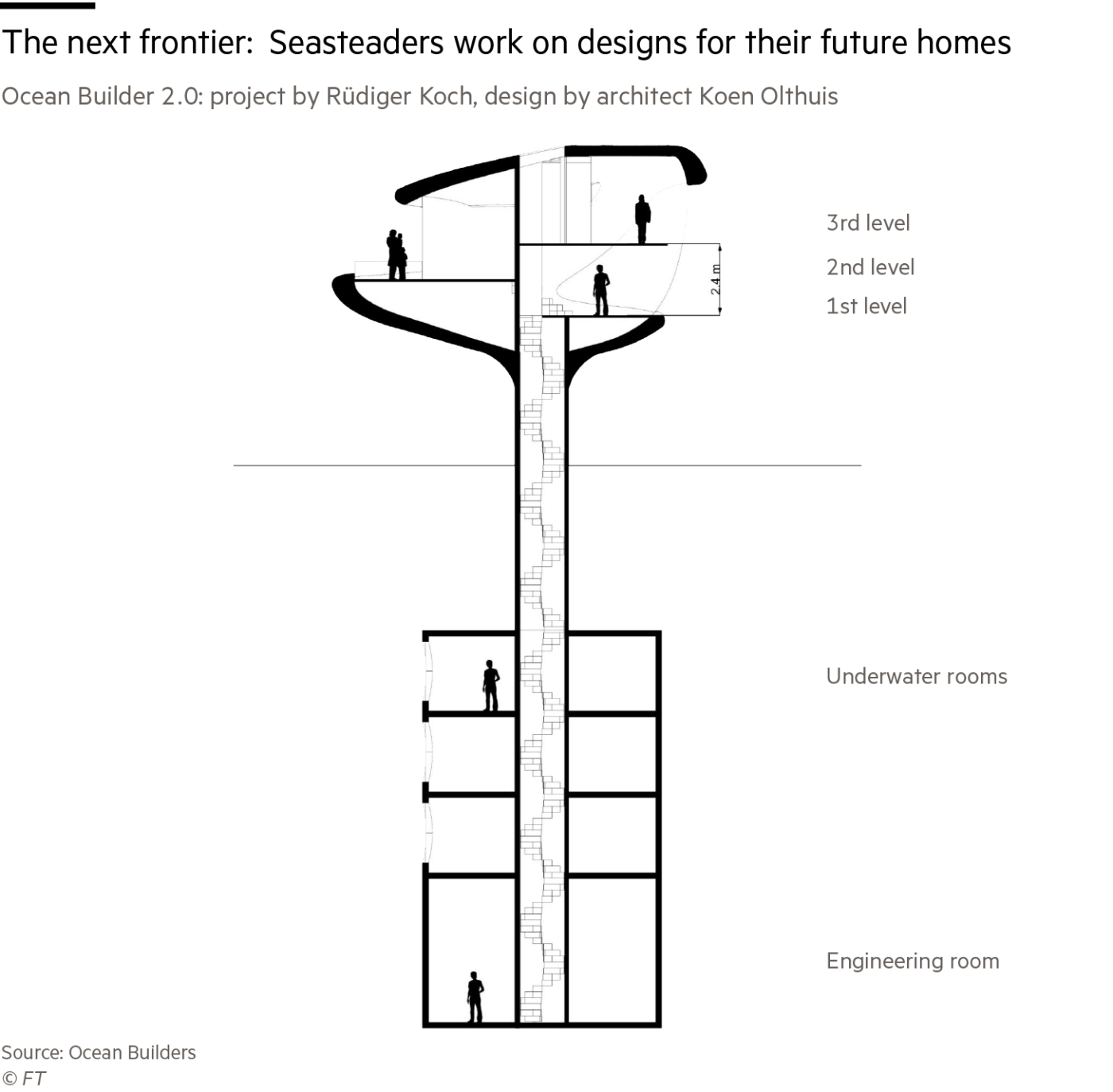

The overlap between escaping catastrophe and simply abandoning society is even more evident in the “seasteading” movement, which aims to create autonomous cities on the oceans. This project was hatched in 2008 by Google engineer Patri Friedman, grandson of the influential free-market economist Milton Friedman, with funding from tech investor Peter Thiel. The idea was that communities floating in international waters could serve as laboratories for new forms of libertarian self-governance, away from the clutches of centralised states. But as the movement evolved into different strands, the rhetoric became increasingly apocalyptic. A group called Ocean Builders, for instance, has presented the floating homes it is designing in Panama as a “lifeboat” to escape disasters such as the Covid pandemic, as well as government tyranny.

These “SeaPods” have much in common with the luxury bunkers back on terra firma. Designed by Dutch architect Koen Olthuis, they consist of a streamlined capsule elevated above the surface of the ocean, with steps leading down the inside of a floating pole to give access to a small block of underwater rooms. They are imagined as lavishly crafted, exclusive products, reminiscent of holiday retreats, with autonomous supplies of energy, food and water. The only problem is such designs need to be trialled in coastal waters, and for some reason governments have not been very receptive to anarcho-capitalist tax-dodgers trying to establish sovereign entities along their shorelines.

But entertaining as it is to ridicule these schemes, there is a danger that it becomes a kind of avoidance strategy. It is not actually far-fetched to acknowledge the possibility of a far-reaching social collapse (on a regional level, it has already occurred numerous times in living memory), and even the United Nations has embraced the speculative prepper mindset. Anticipating the potential effects of climate change, the UN is backing another version of seasteading, with modular floating islands designed by the fashionable architect Bjarke Ingels.

All civilisations must come to an end eventually, and ours is fairly fragile. In complex systems like those we rely on for basic goods and materials, a breakdown in one area of the network can have dramatic destabilising effects for the rest. We have already seen glimpses of this with medical shortages during the pandemic, and soaring energy costs due to the Ukraine war. How far we will fall in the event of a sudden collapse depends on the back-up systems in place. One of the more intriguing figures offering emergency retreats for the wealthy, the American businessman J.C. Cole, is also trying to develop a network of local farms to provide a broader population with a sustainable food supply. Cole witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union the early 1990s, and inferred that Latvia experienced less violence because people were able to grow food on their dachas.

But perhaps the most unnerving prospect, as well as the most likely, is that collapse won’t be sudden or dramatic. There won’t be a moment to rush into a bunker, or to use emergency mechanic skills acquired from Youtube. Rather, the fabric of civilised life will fray slowly, with people making adjustments and improvising solutions to specific problems as they appear. Only gradually will we transition into an entirely different kind of society.

In South Africa, the country where I was born and where I am writing now, this process seems to be going on all the time. There are pockets of extraordinary wealth here, but public infrastructure is crumbling. The power cuts out for several hours every day, so many businesses have essentially gone off-grid with their own generators. The rail network has largely disappeared. Private security companies have long since replaced various policing functions, even among the middle class, and better-organised neighbourhoods coordinate their own patrols. Meanwhile in poorer areas, people still inhabit a quasi-modern world of mobile phones and branded products, but face a constant struggle with badly maintained water, electricity and sewage systems. Housing is often improvised and travel involves paying for a seat on a minibus.

The point is not that South Africa is collapsing – it still has a lot going for it, and besides, most of its population has never enjoyed first-world comforts – but that this is how it might look if, like many civilisations in the past, the advanced societies of today were to “collapse” gradually, over generations. It would be a slow-motion version of the polarisation between survivors and rejects that we see in the escape plans of the super-rich. And though we would realise things are not as they should be, we would keep hoping the decline was just temporary. Only in the distant future, after a new civilisation had arisen, would people say that we lived through a kind of apocalypse.

Anyway, merry Christmas everyone.