Design as Tacit Knowledge

Including: the adventures of Ernst May

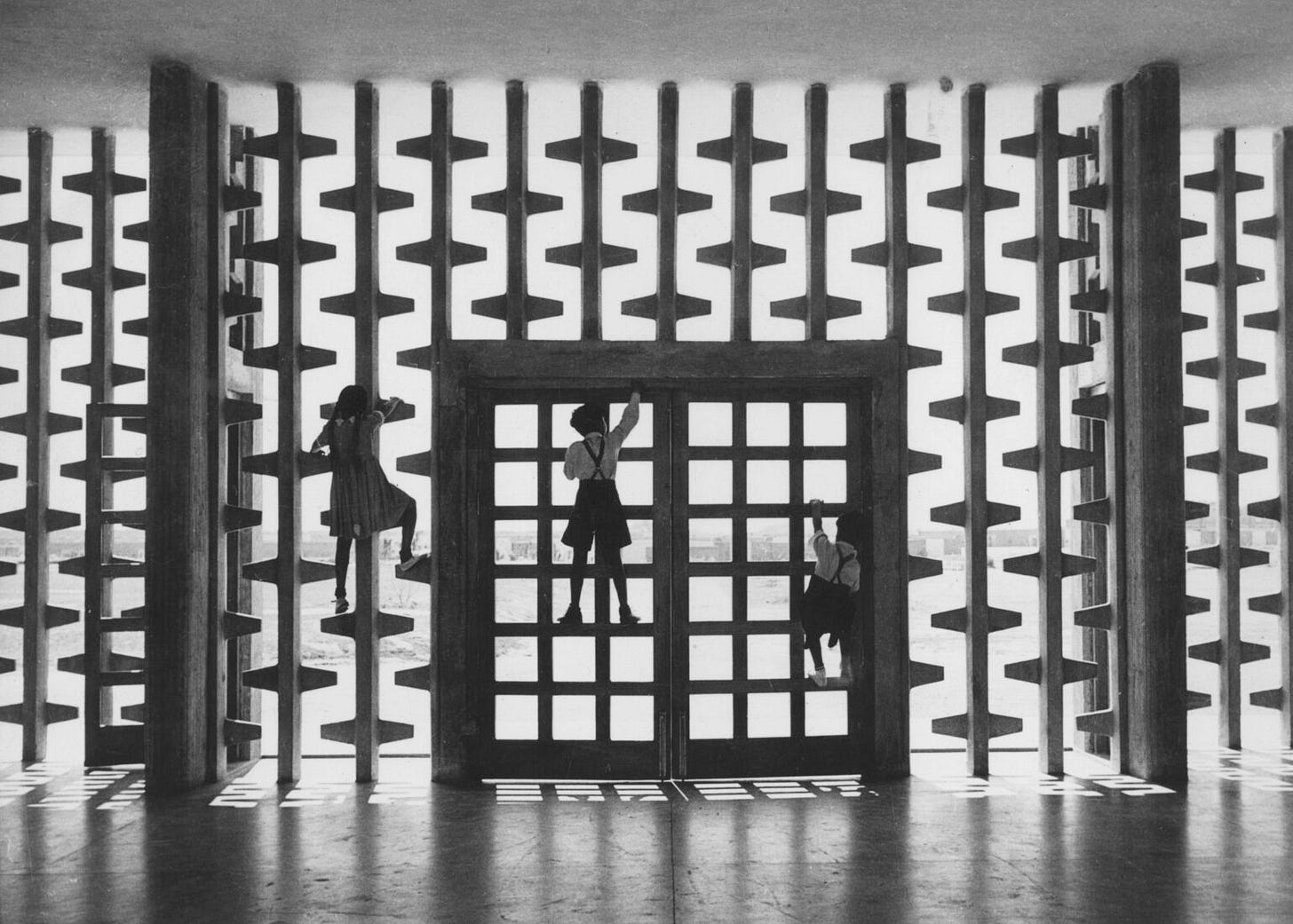

The story of how Modernist architecture conquered Europe after the Second World War, creating new cityscapes of plain geometric buildings, is well rehearsed. Less commonly known is how, in the same period, the style spread to other parts of the world. “Tropical Modernism,” an exhibition at London’s V&A museum, looks at the arrival of Modernism in West Africa and India during the 1940s and 50s. In Ghana and Nigeria, it came via the British Empire, with schools and community centres designed by Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. But after Ghana achieved independence in 1957, the regime of Kwame Nkrumah continued to commission Modernist buildings and monuments. Similarly, it was the leadership of a newly independent India that invited Drew and Fry, along with Modernist kingpin Le Corbusier, to plan the city of Chandigarh.

As I noted in my review for Engelsberg Ideas, “Tropical Modernism” forces us to address the most ambitious aspect of this architectural movement: its universalism. Many of its partisans believed, in the spirit of the European Enlightenment tradition, that it was possible to develop design principles that would be applicable, indeed desirable, anywhere. They understood Modernism as an expression of scientific rationality, objective technique, and an egalitarian assessment of the needs of human beings. For the leaders of post-colonial states, as well as the European architects they commissioned, Modernism was a symbol not of western dominance but of confidence and progress.

There are many reasons to be suspicious of this universalising impulse in design, but I want to consider just one of them. Modernism rarely spread through blueprints, images, or other abstract forms of knowledge. It spread, for the most part, through people. The globetrotting British architects Drew and Fry are a good illustration, but in Britain itself, Modernism had been introduced by émigrés such as the Russian Berthold Lubetkin. Likewise, the style was established in the United States by central Europeans, most famously the Germans Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Even the exceptionally rich and independent Modernism of Brazil was catalysed by a visit from Le Corbusier. After the 1950s, the crucial transmitters in places like India would be students going abroad to study with heavyweight architects.

Like so many transformative innovations in the first half of the twentieth century, Modernism spawned in and around German-speaking central Europe. It spread, in part, because of the ideological convulsions that shook this region, pushing and pulling architects across borders and oceans. Consider Ernst May, who made his name in the 1920s with one of Weimar Germany’s most dramatic experiments in municipal socialism. Serving as chief architect in Frankfurt, May built more than 12,000 units of low-cost workers’ housing, complete with modern utilities and public services. Then, in 1930, May took his team to Magnitogorsk (“Magnetic Mountain”) in the Soviet Union, where he was tasked with planning one of the centrepieces of Stalin’s industrialisation drive: a new city in the remote Urals, centred on an enormous steel works. After several years of struggling with the Soviet authorities, May was ejected from the project, by which time the Nazis had come to power in Germany. So he went to east Africa, where, in the early 1950s, he would design Kenya’s first Modernist buildings, before finally returning to Germany.

There is a difference, of course, between the spread of Modernist buildings and the spread of Modernism as a way of building: the latter requires institutions, whether schools or offices, where practitioners can share their methods. Still, the outsized role played by a small number of architects is remarkable. There is an interesting parallel here with the emigration to Britain and the United States of many of Europe’s greatest scientists – they came from Hungary in particular – which happened at roughly the same time and for the same reasons. One of those émigrés, the physical chemist Michael Polanyi, argued for the importance of personal contact in science. If scientific knowledge was simply the objectively valid statement of universal laws, then why, Polanyi asked, did successful research seem to depend so much on the presence of scientists from a particular part of the world? He concluded that science was really a culture, full of skills, habits and intuitions which could not be explicitly stated, but had to be absorbed through experience. Polanyi called this “tacit knowledge.”

Looking at the spread of Modernism, it appears that design, too, consists of cultures as much as methods or styles. Like all architecture – and like scientific research – Modernism brought its practitioners into contact with aspects of reality that are objective and universal, such as the structural properties of steel, concrete and glass. But as a way of thinking and building, it could become universal only insofar as it ingrained its judgments and assumptions into architects everywhere.