China Is Reinventing the Car

And Europe is struggling to keep up

Over the summer, I came across some startling images in a Bloomberg report on China. The drone footage, captured by Qilai Shen, shows large lots full of abandoned electric vehicles, bumper-to-bumper and wing-mirror-to-wing-mirror, overgrown with lush vegetation. These auto-cemeteries, which have appeared in a number of Chinese cities, are not scrapyards as we know them. The cars are mostly the same models, and look almost brand new, their paintwork immaculate and their windshields neatly adorned with tax and registration stickers.

These images are indicative of how Chinese industrial might has reshaped our relationship with products and materials around the world. We think of cars as reasonably durable things, valuable artefacts that ought to be carefully maintained. The last one I owned, a second-hand VW Golf, was almost twenty years old when I sold it on to its next owner. China’s car graveyards suggest something rather different: automobiles with a lifespan similar to that of an iPhone. The dark irony, of course, is that these electric vehicles were supposed to be eco-friendly products.

What lies behind this is the remarkable story of China’s EV boom. For over a decade, the country’s electric car-making industry has been built up through huge government subsidies and regulations, with the result that China now accounts for more than half of EV sales worldwide. For European countries, in particular, this raises questions not just of economics but prestige: the ability to design and produce world-class cars is a symbol of industrial heritage. When it comes to EVs though, Europe’s legacy automakers are falling behind. China has leapfrogged its western competitors in one of the crucial technologies of the 21st century.

This is most obvious in China itself, the world’s largest car market, where German giants such as BMW, Mercedes and VW have been caught out by the arrival of the electric age. A quarter of cars sold there last year were EVs, many of them made by the new Chinese champion BYD. As for American companies, Tesla still does very good business in China, but BYD has now overtaken it as the world’s top seller of electric cars. Chinese manufacturing is even more dominant when it comes to supplying the world’s EV batteries.

In part, the authorities backed EVs because they wanted cleaner air in cities like Shanghai, and fewer carbon emissions. But this is also a classic case of China’s strategic Fordist state in action. This aim is not to be the most high-tech – EVs are generally less complex in engineering terms than combustion cars – but to secure key resources and technologies, organise effective supply chains, drive down production costs and make things in enormous quantities. China has broken through on EVs for the same reason that it makes most of our smartphones and laptops: it has an unrivalled ability to produce technologies at scale.

In fact, China is so good at this that its economy is being undermined as a result. Its governing class is fixated on generating growth through investment, which comes at the expense of raising the wealth of ordinary people. China therefore produces more than its consumers can buy. Those fields of abandoned EVs are one sign of this unbalanced economy: many of them likely belonged to clean taxi companies that only existed thanks to government subsidies, and duly went bust when the support was withdrawn. Another, more infamous symptom of this problem can be found in China’s millions of unoccupied homes, the aftermath of a real estate bubble pumped up with debt.

But unlike apartment buildings, excess cars can be exported to other places, as happened previously with China’s overcapacity in steel, aluminium and solar panels. In this way, an economic weakness can become a strategic strength, as cheap exports undercut industries elsewhere and tie their market to Chinese producers.

Thus China has recently overtaken Germany to become the world’s second biggest exporter of cars, trailing only Japan, something unimaginable less than a decade ago. Now Chinese EVs are threatening to challenge European carmakers on their own soil. At the recent Munich motor show, almost two-thirds of the floor space was taken up by Chinese cars, while Chinese companies already provide a third of Britain’s EVs.

What, if anything, Europe can do to protect its automakers is still being frantically debated. Given Germany’s need to sell cars in China, the EU is unlikely to copy the United States by imposing high tariffs. But we should equally reflect on the crucial role of design in this contest.

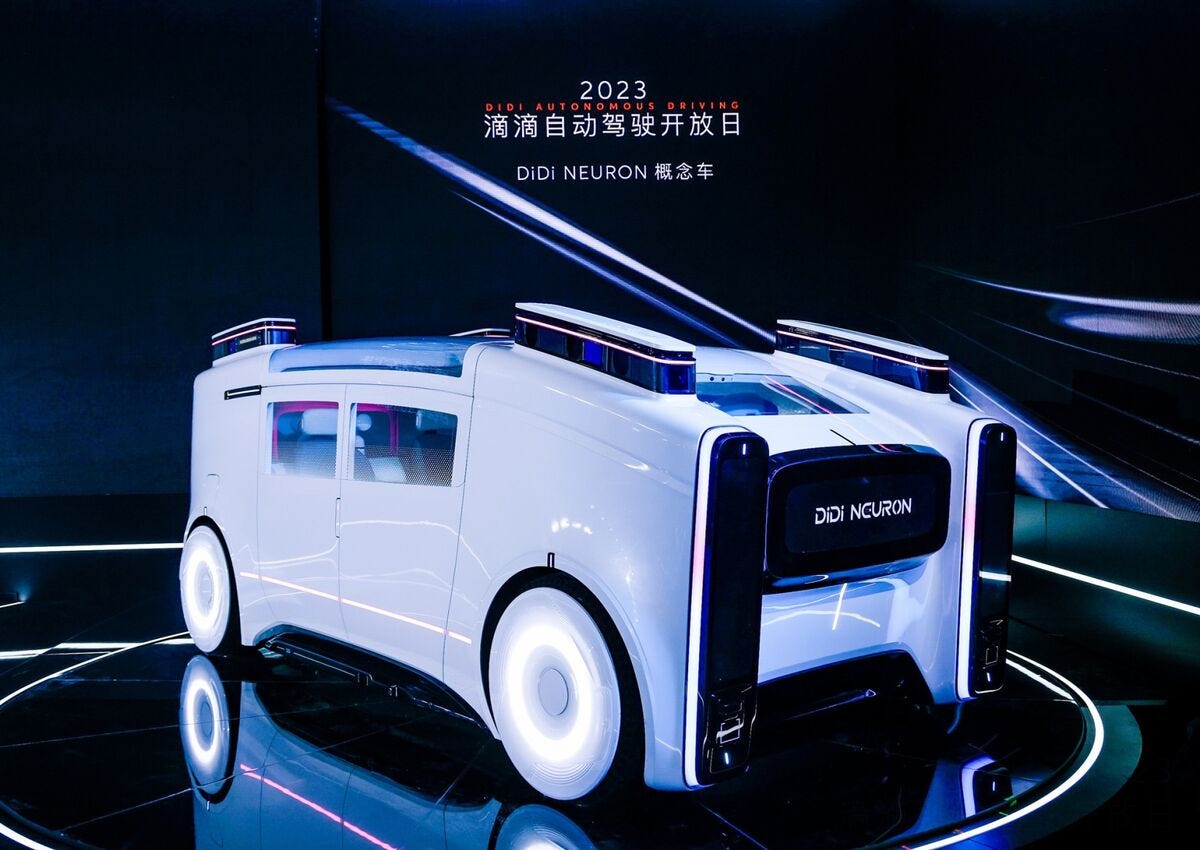

Unlike Tesla, German companies are falling behind in China because they did not adapt to changing tastes. While they have focused on performance and engineering, it appears many Chinese drivers view their cars more like an urban gadget, valuing features such as autonomous driving, AI functions and fancy digital displays. Consider the prototype “robotaxi” that the tech company Didi exhibited in Shanghai earlier this year; admittedly this is a concept piece, but its striking sci-fi aesthetics point to a very different way of thinking about cars that is emerging in China.

BMW, for one, is trying to catch up. Its Vision Neue Klasse model, with a digital display covering the windscreen and sensors to recognise hand-gestures, has clearly been designed with China in mind. Interestingly, it was unveiled in Munich, showing the potential for Chinese preferences to transform cars in Europe too. By and large though, German automakers have been slow to adapt, with numerous “next generation” EVs delayed by software issues. By contrast, Chinese brands are designing a whole range of export cars tailored to Europe’s consumers. BYD alone has produced six models for the European market in less than a year.

Given all this industrial and commercial activity, it’s easy to forget that the point of EVs is to reduce human impact on the environment. Indeed, the stakes in this race are so high because, as things stand, the EU will ban new petrol and diesel cars in 2035, and the UK in 2030. Electric vehicles are certainly a testament to modern ingenuity, but a big part of that ingenuity is turning any situation into an opportunity to make and sell more products.