Arendt on the World of Things

A theory of private enchantment

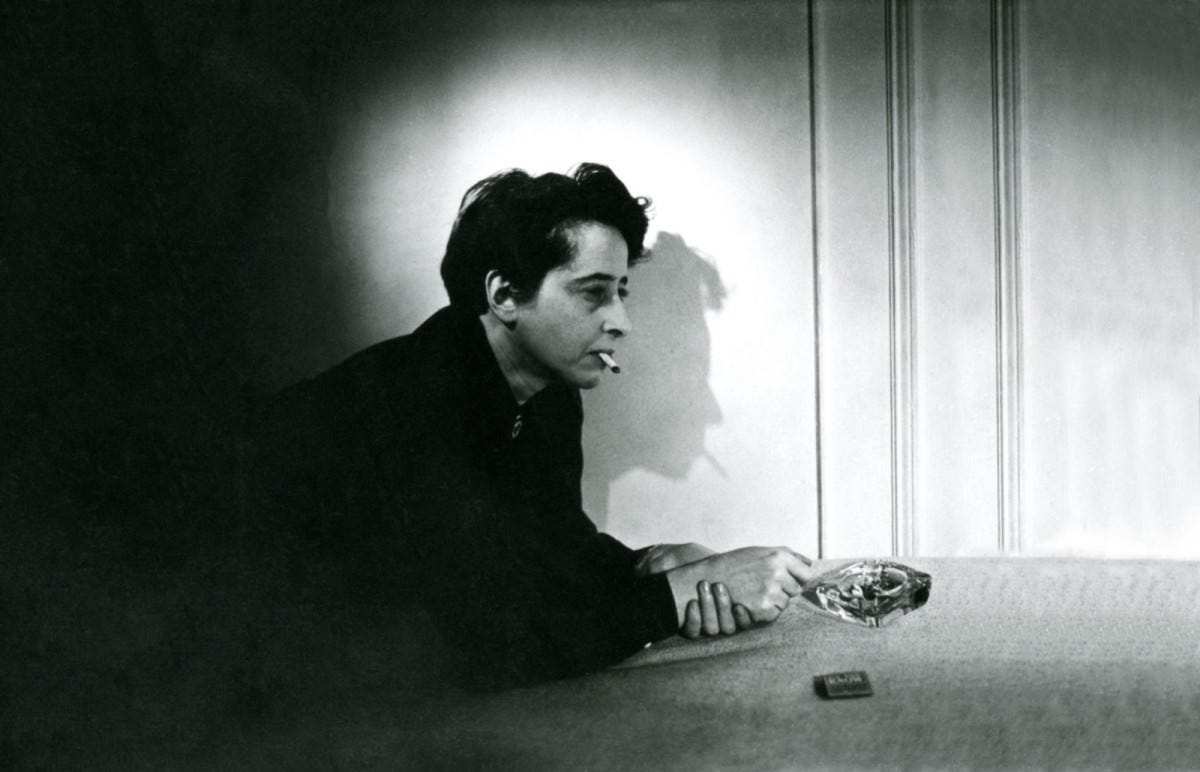

There is no experience quite like reading a book that changes the way you think. Page by page, you feel your mind’s conceptual foundations trembling, then starting to shift and slide; at times every paragraph seems to trigger a small avalanche. It doesn’t happen often, and the same book won’t do it for everyone, but this is one of the joys of reading. Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition did it for me.

Arendt, a German Jew who fled the Hitler regime and ended up in the United States, is best known for her account of the trial of Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann, where she coined her famous phrase “the banality of evil,” and for her earlier book The Origins of Totalitarianism, briefly a bestseller after Donald Trump’s election in 2016. As its title implies, The Human Condition (published 1958) casts a much wider lens on the development of western society. Naturally I can only look at a small part of it here.

Arendt was a political philosopher, but a peculiar aspect of this book is the significance she gives to the inanimate: to “things.” For Arendt, one of the defining features of humanity is that we do not live in nature, but in a “world” of artefacts, manmade structures and objects that provide the setting for our social existence.

Revisiting the book recently, I was intrigued by Arendt’s comments on the distinctively modern relationship to things. It is a deeply intimate one, a special appreciation for private possessions and surroundings, governed by aesthetic qualities such as “charm” and “enchantment.” Arendt finds the clearest example among the French, who, she says,

have become masters in the art of being happy among ‘small things,’ within the space of their own four walls, between chest and bed, table and chair, dog and cat and flowerpot, extending to these things a care and tenderness which, in a world where rapid industrialisation constantly kills off the things of yesterday to produce today’s objects, may even appear to be the world’s last, purely humane corner.

As this extract suggests, Arendt thinks the modern relish for the private sphere is a kind of retreat from, or compensation for, an inhospitable wider world.

Sixty years on, these observations strike me as still relevant. Though modern societies are far from identical in this respect, many do seem inclined towards the enjoyment of a private world of things, whether expressed in a desire to amass personal possessions or to create a perfect home. This is normally attributed to consumerism, or assumed to be an innate human tendency that modern prosperity has merely enabled. Perhaps both are true to some extent. But it has also been observed that what Voltaire called “tending one’s own garden” – seeking happiness in the things we can actually control – becomes more attractive at moments when public life is chaotic or inaccessible.

For Arendt, a genuine public sphere, a “common world,” must by definition provide some sense of permanence. For it is precisely to offset the inescapable reality of change – the rapid cycles of nature and the brute fact of human mortality – that people wish to erect a world of artefacts in which to live together. This world, with its structures, products and tools, provides a bedrock of shared experience that allows people to feel part of something that transcends their own finite existence.

A good way to understand this point is to consider how a novelist or filmmaker typically creates a setting. They focus on characteristic details – the clothes people wear, the style of their buildings and streets, their implements for work and everyday accessories – which communicate the richness of a particular “world” those people inhabit together. In the same way, Arendt thinks the artefacts that surround us serve the purpose of “stabilising human life,” because people are always different, and so can only “retrieve their sameness… their identity” through a shared world of things.

Over the last century, of course, artefacts have increasingly become products for consumption; they are not used and lived with over an extended period, but rapidly replaced. The harsh pattern of the natural world, where everything is constantly dying to make way for something else, has invaded the human artifice that was meant to protect against it. As Arendt writes, “we must consume, devour, as it were, our houses and furniture and cars as though they were the ‘good things’ of nature.” Indeed, since wealth is generated by this constant production and consumption, any kind of permanence is now an obstacle to prosperity.

And so the source of stability moves to the private domain, to the quaint confines of the home, the neighbourhood and maybe the town. Here there is nothing as grand as a way of life that will outlive us, but there can at least be the reliable enchantment of “small things,” of private and familiar pleasures. Consider the frequent protests that redevelopment will cause an area to “lose its character.” Such concerns show that places are valued, firstly, in a private way, as a kind of extension of the home, and secondly, as an escape from wider social realities.

What Arendt could not have anticipated is how the relentless turnover of products has become part of this private experience. Even the most sheltered souls can embrace new things in their own space, because they do so on their own terms. This is an under-appreciated aspect of the digital revolution over the past twenty years; products like smartphones, laptops, and the countless gadgets shipped in Amazon parcels each day have been so transformative in part because they are so personal. The pattern of change has been reversed: it now emanates outwards from the intimate sphere.

Excellent as always Wessie.

"But it has also been observed that what Voltaire called “tending one’s own garden” – seeking happiness in the things we can actually control – becomes more attractive at moments when public life is chaotic or inaccessible." - this was very helpful, I am too quick and eager to assign consumerism to cultural modes of purchasing/acquisition and had not thought of this "other side of the coin".

And I know the wonderful feeling of a book being transformative. Wendell Berry in a single essay often does this to me regularly - but the last book that was outstandingly transformative was James C Scott and his magnificent work Seeing Like a State. His concept of state-induced "visibleness" has been highly transformative to my thought, especially in agriculture.

I sure would like to be in a reading club with you all.