Architecture as Anarchy

The disturbing prophecies of the avant-garde Archigram group

I recently published an essay at Engelsberg Ideas about architecture on the moon and Mars. Granted, this architecture does not actually exist – or at least not yet – but in recent years there has been a glut of proposals imagining what it might look like, many of them commissioned by agencies like NASA and the ESA. In my piece, I try to infer what these improbable designs tell us about modern architecture. Projects beyond Earth offer a chance for fresh thinking, but strangely, they also belong to a tradition of sorts, since architecture has already been inspired by space exploration for many decades.

It was in this context that I mentioned Archigram, an influential group of British designers in the 1960s avant-garde. I’ve been itching to write about the Archigram group for a while now, since its relevance to our own era extends far beyond a fascination with space. What the group did with its eponymous magazine was to put forward a particular vision of modernity in the strongest possible terms – an anarchic vision defined by fluidity, improvisation and radical impermanence. These fantasies have in some ways proved rather prophetic, and so their origins and implications are worth considering.

By the late-1950s, British students had become frustrated with the stagnation of modern (and Modernist) architecture. It was three such frustrated students – Peter Cook, David Greene and Michael Webb – who in 1961 published the first issue of Archigram. They were soon joined by a further trio of architects from the London County Council: Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton and Warren Chalk. The magazine consisted of futuristic, blatantly unrealisable schemes, presented in the sensational style of comic books and science fiction. These ideas were most obviously an attack on the centralising tendency of the post-war decades, when municipal planning officers, housing committees and big architecture firms were rolling out new housing estates and city centres across Britain. But Archigram’s critique went much further. It rejected the very idea that architecture should provide fixed and lasting structures.

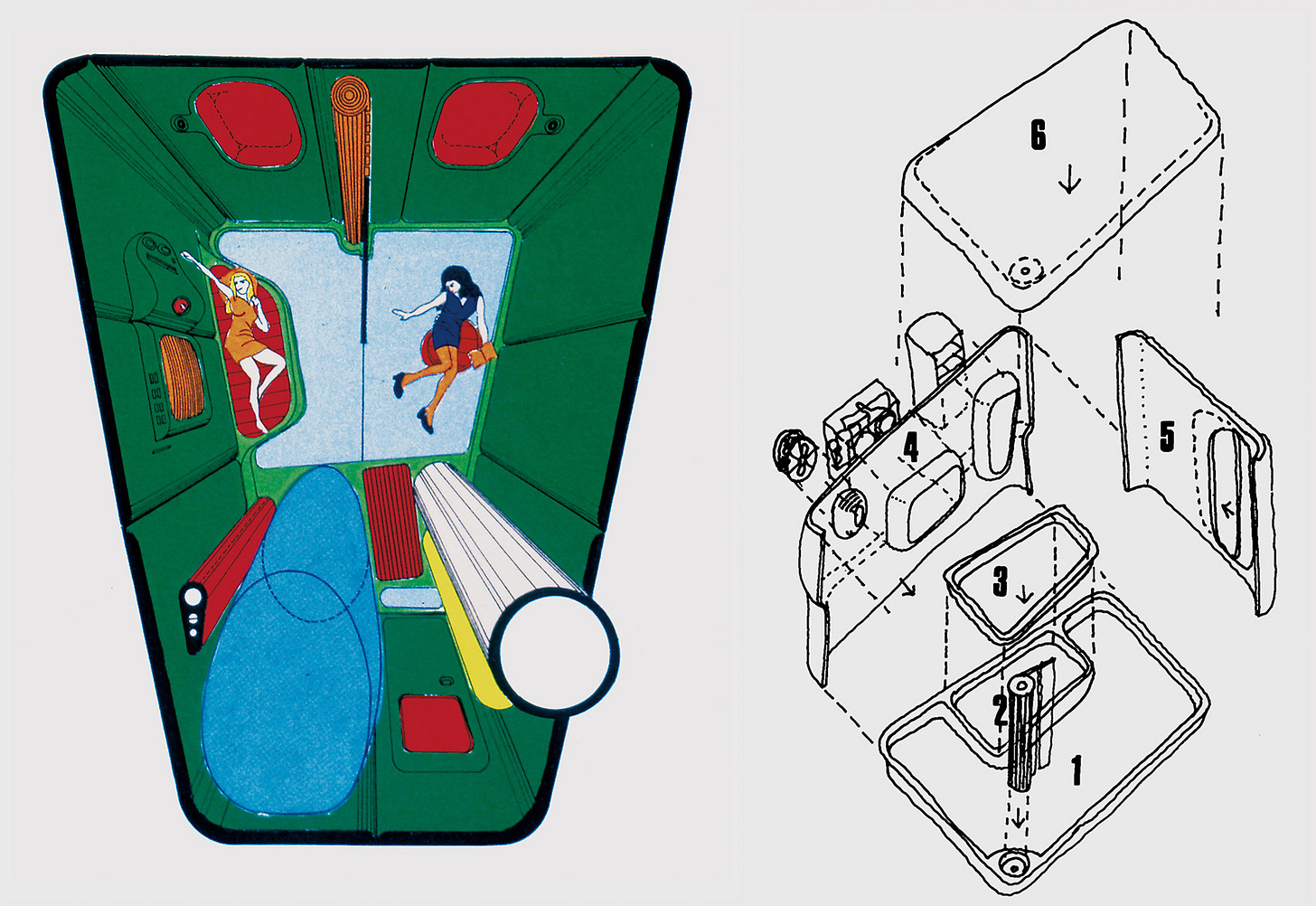

As Archigram saw it, the spirit of the age was defined by technology, consumerism and individualism, and the designer’s task was to harness the first of these forces to facilitate the other two. Architects should not decide how or where people live, but should provide the technological tools for people to fashion their own existence as they see fit. As design historian Simon Sadler puts it, Archigram saw architecture “more like a refrigerator, car, or even plastic bag than an immovable monolith.” They imagined a house as a consumer product, or a kit of parts for each individual to assemble according to his or her needs. They imagined cities as mobile structures, or ephemeral happenings where a nomadic population would gather and disperse at will.

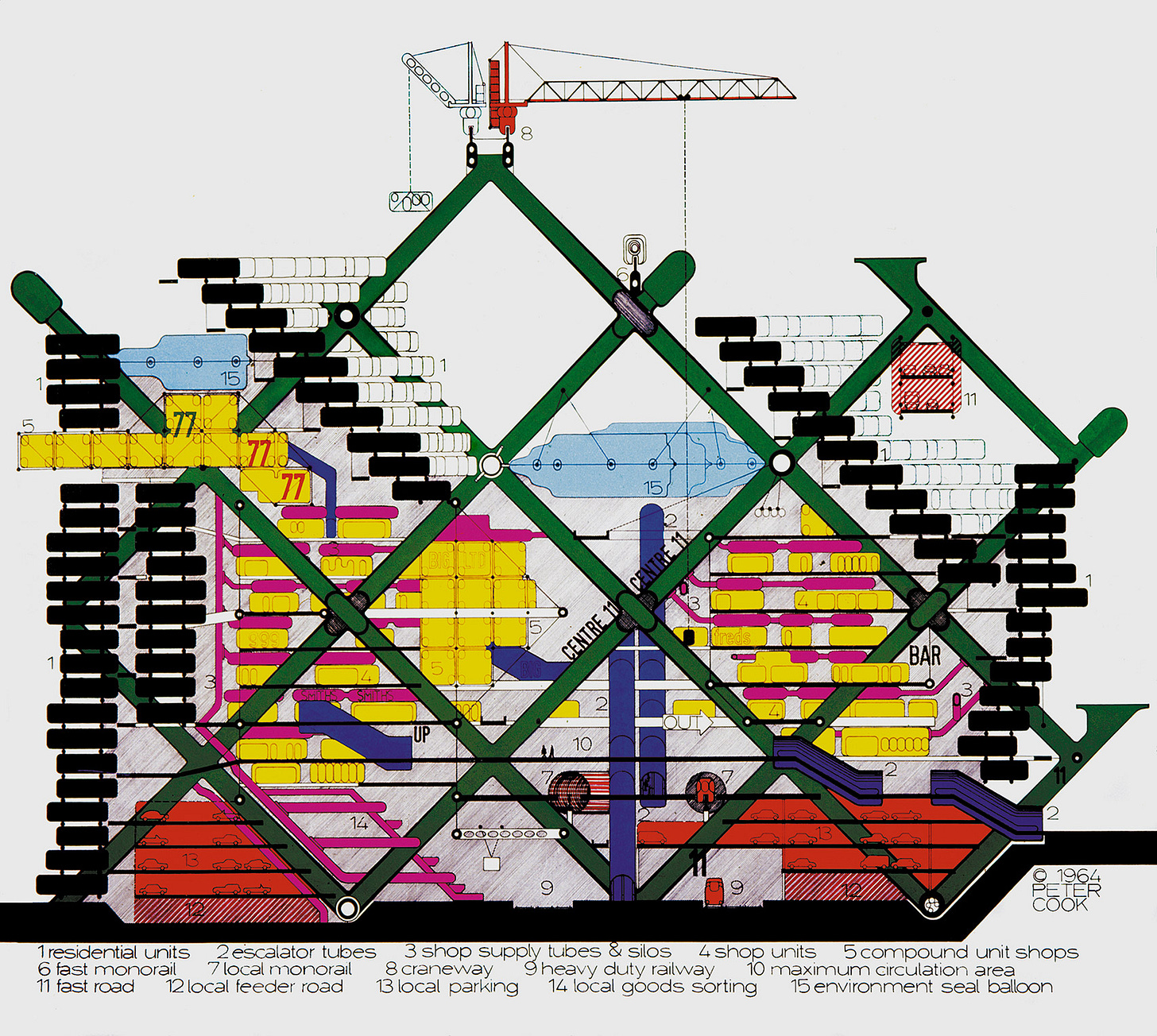

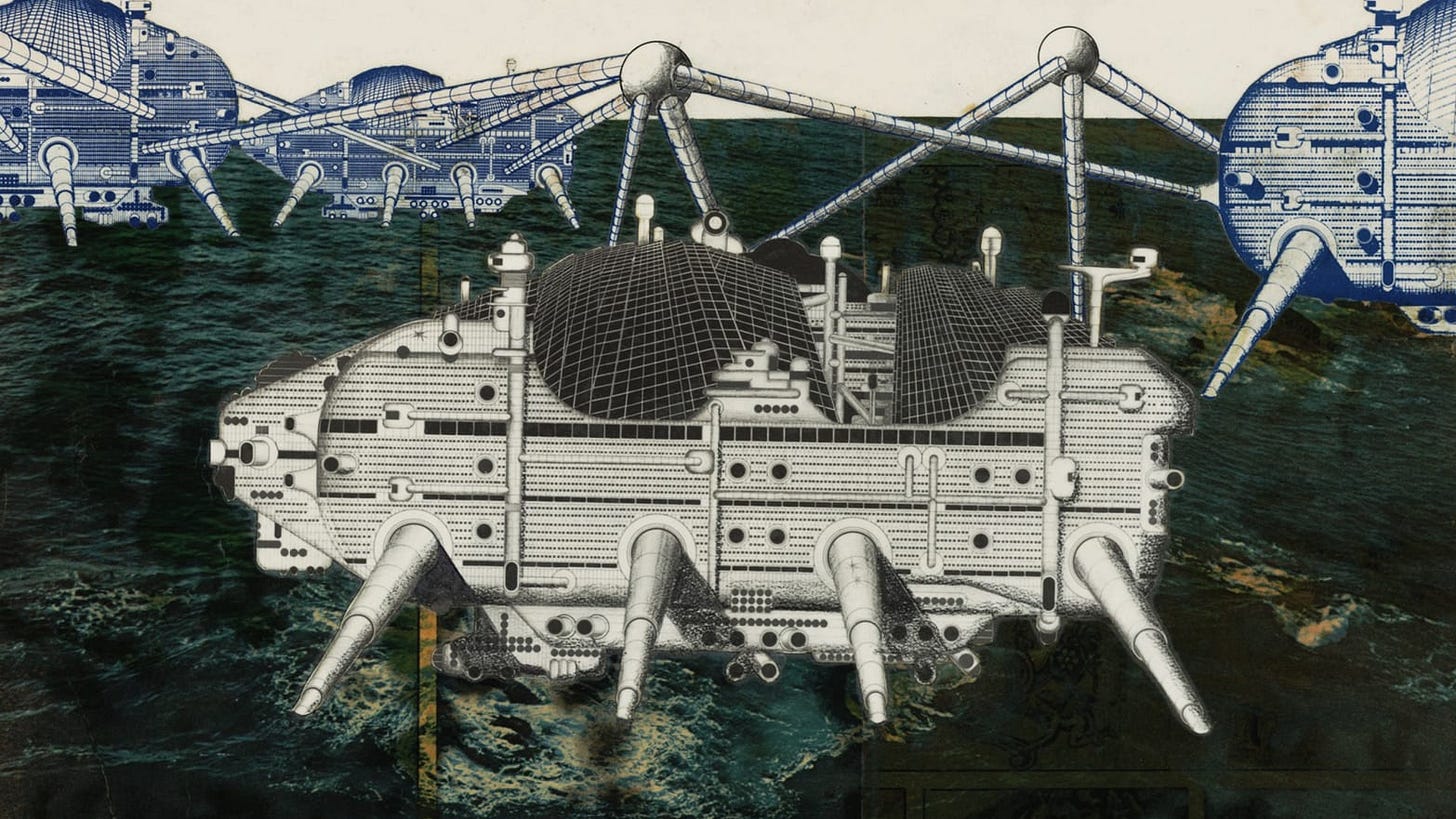

Thus the pages of Archigram portrayed cities that walked on legs, cities carried by airships, even cities that submerged themselves in water. Other schemes included the “Living Pod,” the “Capsule,” the “Gasket Home” and the “Cushicle” – all efforts to redefine the home as an autonomous, high-tech piece of equipment which could be easily moved from one place to another. In projects like the “Plug-In City,” these self-catering mobile homes were attached to tower-like nodes or stacked on top of each other, so that human settlements were replaced by temporary congregations of domestic cells.

The group was obsessed with space exploration because it provided technological precedents for many of these concepts. NASA’s Apollo missions featured lightweight, high-tech capsules as well as large-scale engineering such as rocket launch pads, a duality that mirrored Archigram’s own vision of autonomous pods and superstructures where they could be docked.

It did not take long for these ideas to escape the pages of Archigram and take material form, especially through the high-tech architecture movement. One of the earliest major examples was the Centre Pompidou in Paris, designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano in 1971. The building’s exoskeleton of scaffolding and bulbous pipes, more reminiscent of an oilrig than a cultural centre, closely echoed the group’s drawings in style and spirit. Two decades later, the echoes were still evident when Rogers gave a lecture outlining his philosophy. “I am searching for an architecture which will express and celebrate the ever-quickening speed of social, technical, political and economic change,” he said, inviting a radical break with “the platonic idea of a static world, expressed by the perfect finite object to which nothing can be added or taken away.”

But as this reference to “ever-quickening” change suggests, Archigram’s speculations have proved prescient far beyond the field of architecture. Even if we don’t live in peripatetic capsules, our societies have become increasingly fluid and atomised, expecting individuals to adapt continuously in pursuit their aspirations and to fashion their own identities. The iPhone is the ultimate Archigram product, a mass-produced portable tool that each consumer can use in a different way, maximising flexibility and efficiency. Perhaps the group’s real heirs are those transhumanists who dream of uploading their minds to software, thereby abandoning not just fixed buildings and cities, but the home that is the human body.

There was much value in Archigram’s playful rebuttal of the post-war status quo. Top-down planning of neighbourhoods and urban centres threatened to alienate people from the places they called home, turning them into passive recipients of anonymous, one-size-fits-all environments. The Dutch architect Herman Herzberger has described this problem succinctly: “It is the great paradox of the collective welfare concept, as it has developed hand in hand with the ideals of socialism, that actually makes people subordinate to the very system that has been set up to liberate them.” But Archigram’s alternative vision of empowerment is hardly more convincing. To be free from lasting structures and social arrangements is to be free from the standards of responsibility that these relations sustain, and as such, can only produce a fundamentally competitive world. In this sense, the most eloquent critique of Archigram’s approach comes from the nightmarishly cramped conditions of its own living capsules.

Still more revealing are the apocalyptic currents that course through Archigram’s schemes. Like their hero, the American designer and theorist Richard Buckminster Fuller – and indeed, like our own discussions about colonising other planets today – it was somewhat ambiguous whether Archigram was looking forward to a utopian future or responding to the threat of a catastrophic civilisational collapse. The group’s autonomous, roaming cities and pods were presented not just as technological commodities, but as emergency life-support systems for people condemned to wander across a desolate world. By the mid-1960s, Archigram was explaining its projects in terms of “survival.”

This catastrophism was obviously related to contemporary fears about over-population and nuclear war. But it also reflects the fact that, in a world defined by impermanence and individual agency, there can be little by way of a shared purpose beyond mere survival. Apocalyptic anxiety is merely this same social vision projected onto the horizon of the future.

Fascinating, Wessie. Thank you. For all the familiar problems of overcentralization, the self-proclaimed technologies of freedom so often seem to rely on a creepy underlying structure. The iPhone seems a prime example, spying and revising itself even as the user thinks she owns it. But the urge to escape from politics (the hell of other people?) runs deep . . . keep up the great work.