A Google Architect Speaks for the Masses

The surprising populism of Thomas Heatherwick

Next year, Google will open its new London headquarters in King’s Cross. The building is a true Leviathan: stretching for 330 metres along its horizontal axis, it is longer than the Shard is tall. With its prodigious length and stepped profile, it resembles something between an oil tanker and a vast ziggurat. This comes less than two years after Google opened its no less impressive Silicon Valley campus, a pavilion-like structure with glancing, curved roofs, boasting some 50,000 solar panels.

These buildings are nothing if not imposing monuments to corporate power. And yet a designer on both projects, Thomas Heatherwick, has now declared himself a spokesman for “ordinary people.” In his new book, Humanise, Heatherwick denounces arrogant architects and “the selfish forces of money” for making our streets and cities unappealing to “the passer-by.” It is an audacious stance from a man who has designed luxury apartments in Manhattan and a financial centre in Shanghai.

But if Heatherwick is an unlikely populist, I don’t think he is a hypocrite. Humanise feels like a sincere cry of frustration from the gilded cage of the celebrity architect, one which can be traced back to his teenage observation that “old buildings were almost always fascinating, but new ones were almost always mysteriously dull and monotonous.” More importantly, on most of the major points, Heatherwick is right.

Humanise gets off to a strong start by honouring two masterpieces by the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, the Casa Milà and the Sagrada Familia. These are incomparably beautiful buildings, and Heatherwick’s loving catalogue of their virtues reminded me how thrilling it was to discover them. It’s also clear from the beginning that no image searches will be necessary in the course of this book. Penguin has taken the trend of splicing text with pictures and visual gimmicks to a whole new level here, customising every page with illustrations and different layouts. This often feels infantilising, but it does add an element of humour and lavishness, and this is right book for it.

According to Heatherwick, Gaudí’s buildings are “human.” What he means by this, roughly, is that they provide enough visual complexity to engage the passer-by, they have emotional depth, and they stimulate our sense of wonder and adventure. The opposite of human is not inhuman but, more specifically, boring. Heatherwick claims our world has been ravaged by a “blandemic” of boring architecture. He is talking about the featureless glass and concrete rectangles that dominate the skylines of the world’s cities today. These buildings are too flat, too plain, too straight, too shiny, too monotonous, too anonymous, and too serious.

A good diagnosis, although Heatherwick sadly feels the need to back it up with a slew of findings from the social and behavioural sciences, allegedly proving that boring buildings are bad for us. Some of these studies are worth discussing, but Heatherwick presents them in that cursory, patronising way which seems to say, “don’t worry about judging my arguments, just listen to these scientists.” Of course science is rarely so straightforward, especially in the age of the replication crisis, and it also raises some conceptual problems. Heatherwick writes that boring is just his preferred label for a certain style of building, but some pages later we find him citing Scientific American and “researchers at Kings College London” about medical issues associated with boredom.

Anyway, there is enough evidence from surveys, housing market data, and first-hand accounts to suggest that significant majorities just don’t like the typical offerings of modern architecture very much, at least when compared to older styles. Which raises the question: whose fault is it? Predictably, Humanise blames the legacy of Modernism (“THE HUNDRED-YEAR CATASTROPHE”), drawing a caricature of Le Corbusier to serve as the whipping boy. But the Modernist ideas of the 1920s are not really the issue here. The issue – and this is where Heatherwick really shines – is that a century later, the desiccated remains of those ideas have given property developers an artistic fig leaf for their copy/paste obscenities, a formula for cheap buildings whose sole aim is to maximise returns on land values.

As for the disconnect between architects and popular preferences, I considered some reasons for this in a previous piece. They include professional fashions and incentives, an assumption that architects should lead the public, not please it, and a suspicion of anything “traditional,” lately deepened by culture-war paranoia. Heatherwick makes similar points, but this is where he really cranks up the invective. He brands modern architects a “cult” and “a deluded intellectual elite.” He quotes a sample of Jacques Derrida’s opaque prose, complaining that students are “rewarded for writing and talking in this ridiculous way.” He notes the reflex of some in the architecture world to smear their critics by “associating them with the far right,” and contends that “we shouldn’t be afraid of honouring our culture and the people who built our past.”

The obvious danger of such populism is that it can lead to a view of architecture as mass entertainment, something Heatherwick comes close to advocating when he asks us to imagine “a Wes Anderson office block, a Björk parliament building… or a development of 800 affordable homes by Banksy” (no thanks!). By and large though, the proposals in Humanise are worthwhile. Some are already familiar – design buildings to last centuries not decades; make training more accessible – and some more original, like a return to “pattern book thinking,” whereby designers have a common catalogue of ornament and detail to choose from. But it seems technology is most likely to break the stranglehold of boringness. The next generation of designers will be adept at conjuring imaginative buildings with AI programs like Midjourney, and new manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing will cut the labour costs of realising them.

There are limits to Heatherwick’s vision though, and this is where his background as a globetrotting starchitect comes into view again. His focus on interesting, inspiring buildings overlooks the fact that not every structure can be a statement piece of the kind Heatherwick Studio is famous for. If it was, the resulting circus would be as alienating as a forest of identikit glass towers. We don’t just need interesting buildings, we need interesting styles to build whole neighbourhoods in, and this, more than anything, is what modern architecture seems incapable of delivering.

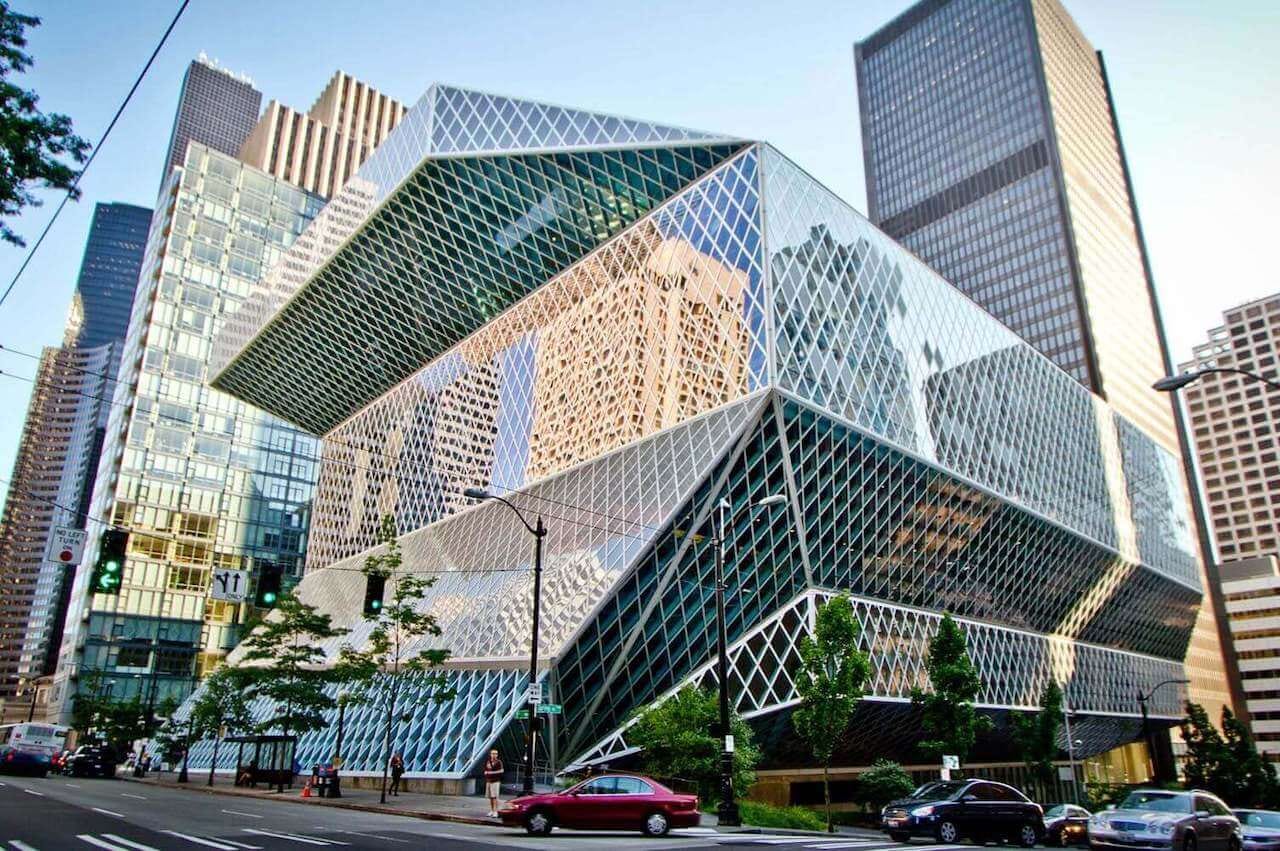

Besides, escaping the Modernist cuboid does not guarantee “human” architecture. The last thirty years have given us countless innovative and formally brilliant structures from the likes of Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, many of which still feel anonymous, remote, and more concerned with power and profit than the passer-by. This is because architecture ultimately tends to reflect the social and economic realities that underpin it. If Heatherwick’s ideas gain traction, the results are more likely to be superficial gestures than a radically new approach to design.

Why, for instance, does the new Google building seem so distant from the philosophy of Humanise? Probably because, while the fashionable Heatherwick Studio and Bjarke Ingels are always named as the project’s designers, the lead architect is actually the corporate practice Building Design Partnership Ltd. Heatherwick’s involvement appears to be less about humanising than human-washing.

I can see this detachment from the ordinary human level in contemporary offices: gleaming, spacious, aspiring to be stylish, but at the level of an individual workstation, lacking privacy needed to focus, and space allowed to be accommodated in a personal style (a couple of shelves around the desk, which used to be a norm, are now gone). Construction technology enables seamless transition between parts of different functions, but the emotional distance between "me" and "my workplace" grows.